26. Psychology And Mentality Of The Animal

A Tungus as we have already seen is a very good observer and he is also a good analyst and generalizer. However, in some cases of observation of the animals when looking for explanation of phenomena observed he himself turns to the hypotheses. Such hypotheses are that of soul which is possessed by animals, put on the same footing as man, and the second is that of spirits which may introduce themselves into animals as they do with man. Here, however, the distinction of the natural phenomena, so understood by the Tungus and European biology, and the phenomena due to the agents of an imaginative order, presents certain technical difficulties for the investigator. First of all the Tungus sometimes are more familiar with the animals, and their psychomental complex, than the European biologists, so that the latter may sometimes mistake natural phenomena observed by the Tungus for hypothetic explanations of an imaginative order. Second, natural phenomena are very often expressed in terms borrowed from the hypotheses regarding the spirits and in the eyes of the investigator they may seem to be mere variations of the hypothesis of spirits, while actually they are not so [149]. In my exposition of the Tungus ideas regarding the psychomental complex in animals I shall try to represent them as they are functioning in the Tungus complex.

The Tungus like to observe without any direct practical aim. It is very unlikely that the Tungus would miss the occasion of observing animals when it is possible. In fact, when a Tungus sees a new animal he will observe its behavior before making his conclusions. If he may observe for a long time the life of animals, even those which are well known to him, he will do it regardless the loss of time, hunger and the hardship of such observations. When the animals cannot notice a Tungus he will spend hours observing them undisturbed. I have been told by one of them that he happened once to discover a female bear with two cubs. Since he approached the den located in a tree, without being noticed, he climbed up to a neighbouring tree and spent there the whole day from early morning until dark, so he might see how the bear mother behaved with her young ones. For a part of her time she was busy in the den, but she did not fall to look out of it when the young bears produced unusual noise. Also she descended from the tree several times for giving food, and once for punishing one of them. During the whole time of observation she was «talking» to the young from her den and in some cases they obeyed her, e.g. responding to her call they climbed back into the den. She taught the cubs how to climb, and to do other things. This Tungus was so much interested in observing them that he did not notice the fall of night.

I have just given this example which might surprise the reader, but it did not the audience of Tungus who added some other facts and they were not surprised at the fact that the man had spent such a long time in the observation of animal family life. It was absolutely natural for them and every one of them would do the same under similar circumstances.

Here is another fact of interest. An old man amongst the Birarchen asserted that there was a bird muduje (one in the water) c'inaka (small birds, chiefly passerers) which dived into the holes in the ice and came out through other holes. The Tungus were a long time looking for an opportunity to catch such a bird. When they succeeded they attached it to a string for observing how it dived, what it ate etc. A group of Tungus observed it very carefully at least half a day. The bird was then killed and examined anatomically; the skin was examined still more closely in order to verify the saying that it had many insects (a kind of louse). In connection with the fact concerning the insects the Tungus have communicated to me at which seasons the animals have these insects. So, for instance, the sable has fleas the year round.

Indeed, every new fact is communicated to other Tungus and in this way the natural history of animals is created as a body of knowledge. When the facts are not sufficient, the Tungus under this stimulus keep near themselves the animals which they do not yet well know. Sometimes one may see near the Tungus wigwam young birds of different species which may happen to have been caught alive. They are not immediately killed, but are left attached to a post by a string. In the same way the Tungus keep other animals but in justification they explain that the animals are kept for amusement of the children, yet the adult people spend their time observing these animals [150].

The Tungus observe all the animals which are met with in the region. However, their knowledge is not equally good of all animals. There are four conditions which are responsible for it; namely, the Tungus pay more attention to the animals on which they are living; not all animals allow man to approach them very closely; the number of animals is different for different species; the animals behave differently towards man and those which are dangerous attract more attention.

A good knowledge of the psychology and mentality of the animals is condicio sine qua non of the Tungus survival. In fact, a hunter who does not know the habits of the animal, degree of the sharpness of ear and eye and keenness of smell, who does not know how strong is the animal, whether and in which conditions it attacks or not, he is doomed to perish either because of his inability to get the animal, or because of the animal itself which very often attacks the inexperienced hunter. Hunting based upon the calculation of incidental meeting and killing of the animals is not dependable and man cannot live on it. Hunting is first of all a difficult profession and when the Tungus goes hunting he always has a definite plan and purpose of killing, in a certain definite locality and even an animal sometimes met before, or to meet a group of animals which may be surely found there. If the professional hunter wants to live on hunting he must know what he wants to kill, and instead of a meat animal he will not kill the fur animals incidentally met on the way, supposing of course that the fur animal is not exceptionally valuable. Yet, he will not kill a wolf incidentally met on his way or any other animal which he is not intending to hunt. I have already pointed out in SONT that the Tungus very often specialize in various forma of hunting and in certain kinds of animals. One of the causes of such a specialization is the knowledge of the animals, which may be acquired by personal experience and by bearing from other people.

Indeed, such a knowledge cannot be based upon the imagination. It must be, as it actually is, very realistic and correct, for mistakes of this kind cost dear to the Tungus. No exaggeration of danger or easiness of the animals' character for the hunter, or lie is permitted by the Tungus. As a matter of fact the Tungus never lie, nor give full freedom to their imagination when they relate the facts and observations regarding hunting or animals [151]. In the society which is not living on hunting «hunting stories» have become synonymous with imagination of not ill natured liars. And most of such hunters a priori are classed so. It shows only one thing, that the life of cities does not impose knowledge and accuracy regarding wild animals. If such a comparison may be allowed, I should say that for a Tungus to lie regarding the hunting and animals is equivalent to a lie of a railway company in its schedule of trains, — it is merely impossible. The Tungus liar, or merely a man who imagines stories, would lose his social position and would be looked upon as an abnormal person.

When I describe the Tungus as excellent observers and men of discipline, I do not intend to say that they never mistake, never over- or underestimate animal character, never propose wrong explanations of the phenomena observed. Certainly, they do. Later on we shall see that in some respects the Tungus cannot solve problems without help from the hypotheses, but what they know about the animals far surpasses what is known to people who do not live on hunting.

First of all the Tungus recognize that animals possess certain mental abilities which may sometimes be superior to those of man, but which are usually inferior, and at least in some animals reduced to such a minimum that the Tungus are not sure whether or not these animals have any mental activity. However, those animals which possess a high mentality, even superior to that of man, are not like man, for their mentality is different. For instance, the tiger in Manchuria is considered by the Tungus as a very intelligent animal. In fact, this animal may easily lead the man on a false track and when the hunter loses the tiger from his sight it may follow the hunter and kill him at any moment. Therefore when hunting this animal the Tungus are very careful. It will be later shown what they do in order to escape the tiger's attack. The leopard also is considered as very clever animal, especially owing to its method of attacking by jumping from the trees, but the Tungus do not know this animal as well as they know the tiger. However, if one asks the Tungus which is cleverer: the Tungus or the tiger, they would say that the Tungus are still cleverer than tigers for they kill the tiger and in some respects the tiger is «stupid».

The bear is considered as an intelligent animal but not to such a degree as the tiger, for the bear has some habits and certain psychological characters which make it very easy for hunting. However, the Tungus recognize that the bear is more intelligent than the tiger e.g. as it would be seen from the above mentioned female bear. Different species of bears possess different mentality, so that for instance the small Tibetan bear is considered more intelligent than the brown bear.

The cervines, except the domesticated ones, are considered as much less intelligent than the tiger and bear. The wolf together with the badger on the contrary are considered as stupid animals. The horse is not so intelligent, as the reindeer; and the cow, where it is known, is considered as a stupid animal, while the mentality of the dog is equal to that of man, at least in some respects. Amongst the fur animals, the sable is considered as very clever animal, while the squirrel is much inferior to the sable; however, the Tungus do see a sign of high mentality of this animal in the fact of its storing food for winter. The birds are classed too, — some of them are considered as inferior, e.g. the eagle, while the others are considered clever, e.g. the raven, for the latter may cooperate in hunting [152].

Yet, the Tungus recognize that animals have certain individuality, and some of them are more and some others are less clever. For instance, if the tiger does not show its usual ability of «cheating» the hunter, it would be considered as «stupid», so as in the case if the tiger does not understand that the hunter does not intend to interfere with the tiger's affairs (vide infra). The same is true of other animals, especially dogs, reindeer and horses. It ought to be here noted that the Tungus do recognize that the animals may become placings for the spirits. If it is so, then also the animal may become «stupid», «unreasonable», or being actually directed by the spirit it may become as clever as the spirit itself.

When one wants to understand the Tungus attitude towards the animals it is important to keep in mind, that the animals which are not well known to the Tungus are very often supplied with imagined characters. Here folklore in the narrow sense of the term (vide supra Chapter III) may be a source of enlightenment, especially alien folklore, which sometimes may be understood as a reliable source of information. In this respect the Manchu ideas regarding the animals psychomental complex are very typical. In fact, the Manchus being chiefly agriculturists have already lost their connection with the hunting complex and the knowledge of animals amongst them plays the role of passtime or distraction. Into their complex they adopt all kinds of information and particularly from the Chinese books and novels. So generally among the Manchus one may find the most extraordinary stories about the animals which the Manchus accept as true stories. For instance, the famous fox-stories of the Chinese folklore and literature are accepted as facts. The same is true of the Tungus groups which become disconnected with the groups living on hunting. This is the case of the Birarchen settled in villages. In the same position are found the Northern Tungus of Transbaikalia who now live on cattle breeding.

* * *

The observations of the life of the tiger and bear have brought the Tungus to the idea that these animals may in some respects be treated in the same manner as man. The Tungus recognize that these animals would not attack the man if he does not want to harm them. So in order to make the tiger understand that the hunter does not intend to interfere with the tiger's hunting, the man must leave his rifle, putting it on the ground, and address the tiger with a speech in which he states that he will not interfere with the tiger's interest in the region that he only visits it on his way to his own hunting region etc. The tiger is supposed to understand not word by word because the tiger cannot speak, but by a special method of penetrating into the sense of the speech.

The facts of speaking to the tiger are known from other regions too. So, for instance, V. K. Arseniev relates about it and under similar circumstances in his records (cf. Darsu etc.). Here it ought to be pointed out that the speaking to the animals is observed amongst almost all peoples of the earth. However, the purpose and ideas are not the same. If one takes all formally similar cases together, then one may confound the facts of different origin and function. I will not now go into the details which may take us very far, but it must be pointed out that the same Tungus do speak sometimes to themselves (psychologically this is the case of monologing), they do speak to the implements although they do not believe in the existence of soul or mentality in the implements and the latter have no special spirits. Yet, the Tungus would speak to an inanimate placing for the spirit (which may be especially made, or may be a tree or a rock), but he will speak to the spirit and not to the placing for the spirit. These are different cases of «speaking». However, in the case of speaking to the tiger he actually speaks to the animal with the intention of being understood. The ethnographers very often, if not usually, take for granted that the «primitive» people believe that the animals understand human speech as men do. It is not so, at least in reference to the Tungus in the case of their speaking to the tigers. According to the Tungus, the animal does not understand word by word, but it grasps man's speech in the sense of the man's behavior. In fact when meeting a tiger without any intention of fighting it, the Tungus must speak something and with a certain sincerity in order to be trusted by the tiger. Naturally in a similar case he would remember what he had heard from the experienced hunters and he would repeat more or less exactly the sense of the speech heard by him. Under certain circumstances it may take the form of pure convention and even degenerate into a «magic» trick. Thus, one cannot take this case as evidence of the fact that the Tungus believe in the tiger's ability to understand human speech in general. The other facts mentioned above and to which we shall return, have entirely different meaning and function in the Tungus complex. I think that all similar facts must be carefully analyzed before being used for generalization like that of a recent writer on this question who trusting himself to the scientific reliability of Sir. J. Frazer inferred «the primitive man attributes to the animals the understanding of human language» which he needs for developing his own variation of Sir J. Frazer's theory of taboo [153]. I do not deny the possibility of such an attribution amongst some ethnical groups and in certain conditions, e.g. as a special theory or as a magic method etc., but I cannot agree that this is a typical «primitive» character. Indeed, it is a late and secondary inference, perhaps a new adaptation of badly understood cultural elements borrowed from the original inventors.

If the tiger is not «stupid» he will leave the man alone and the man does not longer need to think about the tiger, — the tiger will not attack him. The Tungus believe that the tiger is not friendly to the man, but the tiger does not dare to fight man for the latter is well armed. Yet, the fact is that the Tungus when behaving unfriendly towards the tiger may be attacked by the tiger, — what happens rather often with inexperienced hunters. Owing to this the man must demonstrate before the tiger his peaceful intention as shown. The Tungus believe, — and it seems to be a matter of observation, — that the tiger recognizes his RIGHT ON A CERTAIN TERRITORY which cannot be harmlessly visited by the man, or large bears as well as other adult tigers. The tiger would not attack the man or large bears outside of his own territory and he will not attack the man or bear on his own territory if they do not show hostility. The tigers, bears and many other animals, according to the Tungus, know perfectly well the meaning of the fact when, the man is armed with a gun, or with a spear. The same recognition of territorial right is supposed to exist amongst the large bears. The Tungus of Manchuria are inclined to see the idea of property amongst the small bears too, when they put their marks on the trees (by biting them) located at the radius of 25 or so metres from the den. They do the same with the entrance to the den if it is located in a hole of a tree. So the Tungus find the bears when they want to hunt them. A recent biting is recognized by the freshness of the bite which becomes gray after the period of summer rain. Other bears do not disturb the bear which already hibernates. However, if marks are put on the trees for indicating the region occupied by the bear, a fight between the two bears is possible. Again, as I have pointed out (SONT), this is used as a method of finding animals. The Tungus also recognize such a distinction of ownership of territory and they would not go into war with their neighbours, — the tigers and bears, — unless they are forced to take away the territory occupied by them. In the Tungus mind it is a war. According to the Tungus, such a war is very dangerous because the bears or tigers may destroy the family of the hunter and his domesticated animals during his absence, while he cannot stay all the time watching his family and household. The ownership of territory and non-attacking policy, are recorded in different parts of the world - e.g. in Africa, Canada, also in the Maritime Gov. — so they seem to be a fact. The complexity of relations between the man, tiger and bear, as I have described in SONT, is thus only a particular case of local adaptation of these animals, in the midst of which the Tungus does not underestimate and probably does not over-estimate his own power of control of the territory and thus he remains a realist. The methods of arranging relations with these animals are gradually worked out, and they are effective as an empiric solution of the problem. Yet, when a Tungus speaks to the tiger, he leaves his gun down etc. and does not believe the tiger to be a being endowed with supernatural power. He hopes to be understood but if he fails he has to fight.

It is different with the BEAR which cannot understand speech. However, if the Tungus is not armed — which is usual with the women and they are not afraid to go alone — the bear would not attack him. Yet the bear may be frightened by something unusual and may lose his ordinary way of acting. So, for instance, a Tungus (Nerchinsk) meets a female bear with a young cub, and since he knows that the female is dangerous and he has no cartridge in his gun, he takes his gun in both hands and begins to beat a tree with it and to cry with a harsh voice. The female bear is surprised at his at attitude and retires, while according to her usual behavior she would attack. Therefore the Tungus say that the bear is not as intelligent as the tiger which cannot be surprised by such a simple trick. The bear cannot be killed at once unless it is hit in the heart. Practically it is almost impossible to do this unless the bear stands upon its hind legs and leaves the chest exposed. The bear as a matter of fact does this when it approaches the man for attacking him with its paw. But some of them rise up too late for enabling the hunter to shoot, so the hunter has to do something unusual to make it stand up at a certain distance. Sometimes the Tungus begins to dance and cry which produces the necessary effect on the bear. The intelligence of the bear is seen by the Tungus in occurrences which happen from time to time with some. Tungus when they are attacked by the bears. After a successful attack when the man is down the bear considers first by smelling and carefully looking whether the man is alive or not. If it believes that the man is dead it will bury the man supposedly killed, under a pile of the trunks of trees, of shrubs, leaves and earth; then it will again return and verify whether the man in there or not and at last it will leave the place. Naturally the man under such circumstances must do his best not to show he is alive.

The intelligence of the bear and tiger is seen in their ability to know those people who were touched by them. Here the theories and observation of facts and inferences cannot be surely distinguished so I will confine myself to the statement of facts. The Tungus of Manchuria assert that these animals, especially the bear, as a rule attack the people who were once attacked by them. On my question how these animals know it, I received a definite reply by their smelling. The things which have been touched by them are also recognized in the same way. The term used by the Tungus of Manchuria is gdlegda, and the act of touching galenk'i [they may be found in other dialects as derived from the stem nale). The stem is gale (ngale) — to fear, to be frightened. In reference to the man they say s'i gdlegda boje b 'is 'in 'i «you galegda man are»; and the hunting rule is: gdlegda jakava osin gada, — the galegda things one does not take (with on going to hunt) (Bir.) [154]. In it's further extension the idea of gdlegda resulted in the hunters' avoidance of persons touched by bear. Yet, as a rule (amongst the Birarchen), the things touched once by the bear must be buried with the man who was touched by the bear. Yet the Tungus avoid touching the trees bitten by bears. The hunter who did not succeed in killing the animal and who was touched by it, is recommended not to hunt these animals any more, for he is not fearless, he is gdlegda. Perhaps in this case the chief reason is that the hunter possesses no special ability for hunting these dangerous animals, or even perhaps he becomes unable to do it owing to his previous unfortunate experience.

When the bear attacks the hunter and if it succeeds in taking possession of the spear or gun, it immediately breaks the arms. This fact is also considered as an indication of a special intelligence of the bear. In such a case when the Tungus are informed of the bear's attack they go well armed and with the dog immediately to meet the animals aggressors. This attitude could be compared with the custom of vendelta, but I do not want to insist upon it. In the same way the Tungus recognize the intelligence of the bear in the fact that bears store food in the earth and carry it from one place to another until it is finished. However, they say that the bears are not good to their young for which they do not leave food (meat). So that some Tungus call bears «dirty», «bad-natured» animals, for the bear finishes all its food alone, and it is often found overburdened with the food, and asleep, at just the place where the food is stored. Similar facts incline some Tungus to the idea that the bear is not very intelligent but the other facts convince them that the bear is not a bad hearted animal, and under certain conditions can be trusted, e.g. the bear very often collects berries at a short distance from the women also gathering berries. Thus according to the Tungus the bear is intelligent enough to understand the real danger for himself. The Tungus know that the bear is fearful when surprised which may result in spontaneous excretion of fecae which makes the animal very weak. They know the peculiar character of the bear when it hibernates. It may be stated that the Tungus know all the steps in the life of this animal which they recognize as possessing certain rights of life and territory, which they consider as a more or less intelligent being, possessing a soul as man does, possessing certain peculiarities of character. Naturally when the Tungus needs to have a bear skin, and meat he would not hesitate to kill it, but if he does not need them he would not do it, for according to the Tungus idea of hunting — as it is a professional point of view -there is no need to kill an animal if one does not need the meat or skin. The abstaining from killing the bear is based upon this practical consideration and lack of experience of hunting this powerful and intelligent animal.

The behavior of this animal shows to the Tungus that the bear has a soul, which will leave the body, after the bear's death and as any other soul it may harm the man if he was wrong. Hence there are complex customs connected with the managing of the bear's soul. This complex is increased with the other elements borrowed from various groups. If we add to this the aesthetic side of performance and its justification, then we will have the complex of ceremonial eating of the bear, its funeral in the form of exposing the bones (as the Tungus did with man's bones), cutting off the furred skin on the legs, prohibition to the women to sit on the bear's skin and at last prohibition to the women to eat bear's meat, some dancing and singing, which formerly followed the human funeral perhaps. The partial abstaining from eating the bear's meat in the conditions of Transbaikalia and Manchuria is not of great economic consequence for the bear is rather rare and cannot become an essential component of the daily food [155].

Amongst the Birarchen and Kumarchen, bear hunting is no more professionally practiced. Formerly the hunters used to preserve the bones and skin from the head and also paws, on a special platform, and to ask pardon to the bear's soul. At the present time the Tungus usually cut off the head and leave it on the platform or hung up in a tree but they do not practise other customs and they bring back everything which can be carried. Sometimes only the skull was painted in black and fixed on a post. Yet many Tungus do not observe even this custom and they throw away the head, while the heads of other animals are brought home. Owing to this it is difficult to buy complete skins of this animal. However, the Tungus give up even this custom and on special request they may bring the whole skin. The Tungus folklore is very rich in stories concerning this animal. The Tungus accumulate them from the Chinese books and also other ethnical groups, e.g., for instance, the Goldi. Yet, the Tungus do appreciate the bear's meat, but they are somewhat reluctant to eat it as well. However, the introduction of prohibitions may be due to considerations which have nothing to do directly with the special aspects of the Tungus psychomental complex, in so far as it is connected with various hypotheses. Since the Tungus make a kind of sausage of the blood of animals, as Cervus Elaphus, reindeer, and other big animals, they formerly used to make the same of the bear's blood; — it was considered a good dish. However, the taste changed and now e.g. the Birarchen make no sausage of bear's blood, so this abstaining is quite modern, while the explanation is that during the summer the blood of bear has a bad smell wa (Bin), which the old people did not notice before. If one now eats such a sausage «the people will laugh». Indeed, in the eyes of some observers this «prohibition» would appear as one of «religious» prohibitions.

Here I give an illustration of how the ritual complex is built up and maintained. The Birarchen when the bear is killed during the hot weather, after the animal is skinned and dissected into large pieces, cut off the sublingual bone and throw it away. The reason is that if the bone is not cut off, worms about 10 or 12 centimetres long, will infect the meat (the meat is preserved). If the bone is cut out, the worms will concentrate in the cavity and may be easily destroyed. According to the theories, the people who do not know that this must be done only during the summer months sometimes do the same during the cold weather. Indeed, first of all this practice must be carefully investigated and it must be found out how far the Tungus explanation holds good, whether it is a «rationalization» or is based on the facts observed, whether it is connected with some special theory regarding this bone, and soft tissue attached to it, or is a mere meaningless rite.

The bears are called by different names. So we have in Manchuria three species: the tibetan bear — vagana (Bir.); the common small brown bear — moduje (Bir.); the large grisly-like — turni (Bir.). The etymology of the first name is not clear. The second moduje is mo — the tree + du (locativus) +je (suffix commonly used for making of a similar combination a «noun») — it may be thus translated: the one living on the tree, which is characteristic of this species. The third one is of the same type: turni — «of ground», or living in a den in the ground which is also typical of this animal. It is evident that in these cases we have names for different species, but there is no special term «bear». Yet, both moduje and turni may be referred not only to bear's. It seems that the term «bear» is now out of use amongst the Tungus. Yet, we meet with the same situation in other Tungus dialects in Manchuria. In Manchu it is lefu, and in Goldi it has different names of the same type as amongst other Tungus groups discussed below. In Transbaikalia, the general name for bear is man'i (Ner. Barg.). This term is sometimes confounded with another one, namely, magi which means the mythological class of heroes and perhaps spirits. Besides these there are numerous other terms, which may be classed in two groups: names in which there are pointed out some humiliating traits of these animals, e.g. soptaran (RTM) — the one who empties himself of berries; kognor'jo (Mank.), - the «blacky»; hobai (RTM) — the one who has an ugly (hideous) appearance; urgulikkan (Bir.) — the «heavy» one etc.; and the names referring to the honourable persons, e.g. sagdikikan (Khin.) — the old (man) (a diminutive form from sagdi — old); atirkan (and atirkan if it is referred to a female) (also atirkanga) (Bir. Kum. Khin. RTM. and others) whence atirku (Ner. Barg.) which is a term referred to honourable persons compared by me (SONT) with «madame», «monsieur». Yet the bear may be called ama (Bir.) the father or the grandfather) and on'o — the mother (and the grandmother) which are terms referred to very honorable persons. There are many other terms e.g. satimar, (RTM) — «the bear male» which seems to be a Tungus adaptation (mar) of the Yakut term; ayakakun (RTM) — the father, which is a Tungus adaptation (-kakun) of the Yakut term aga — the father; and several other terms which I do not venture to interpret, e.g. derikan (Turn.); keyapti (Urn.); ngukata (Neg. Sch.); sapsaku (Ur. Castr.); bakaja (Neg. Sch.) (perhaps from baka to «find», i.e. the one who is found by the hunter); n'on'oko (Bir. Kum. Khin.) which is perhaps «the great baby» (n'on'o — the baby) [cf. R. Maack op. cit. p. 49. — n'anng'ako (Kum.) — the interpretation is wrong]. E. I. Titov (Some data on the cult of the bear among the lower Angara Tungus of Kindigir clan, Siberian Zivaja Starina, 1923, p.p. 92-95.) gives satimar — (Ner.) which he compares with sadamar (Buriat) — «alert — strong» (Podg.), which does not look likely, considering RTM satimar, taktikaydi — one who lives in a cedar forest; oboci, which cannot be connected with Mong. ebei and translated as «terrible» owing to the suffix ci which means «having», in this case it would be «fear» [cf. also abaci (Eniss.) and ebiko (Eniss. Ryckov) which are terms of kinship (cf. Mongol aba — the father); the form ebiko is a term translated «the grandmother» — the female bear], ngalenga — cannot mean «four armed» for it means «fearful», etc.; sapkaku (cf. M. A. Castren's sdpsdku) — is a doubtful record and translation. For this reason, other terms translated by E. I. Titov such as boborowki, nataragdi, uc'ikan for which there are no corresponding words in E. I. Titov's dictionary and which I cannot justify by my own dictionary, I refrain from discussing. As it is common amongst most of ethnical groups familiar with the bear, the names used during the hunting and during the traveling in the taiga are different from those commonly used and they are not direct names for the bear, e.g. sagdi, ama, atirkan etc., and yet the names sometimes are of an ironical and even offensive character. Naturally the bear in the Tungus complex cannot be considered as a «sacred animal, or «ancestor-animal». The styling of the bear as «father» etc. is merely a «polite form». Yet, the Tungus have no fear to speak or to joke about it.

The question as to why the Tungus have such a long last of names for the bear, and why the original names sometimes disappear, just as it is observed e.g. in some European languages, may be explained by several possible hypotheses. I think that there are different reasons. For instance, some terms used in the joky stories about the bear are not naturally used when the hunter goes for a serious work such as a dangerous hunting. This behavior is characteristic of all peoples and not only in reference to the hunting animals. Another case may be that of a special language used in hunting, and not because of fear of spirits but because of the existence of such a custom in general. What was the original cause of the existence of such a language may also be answered by several hypotheses which may be more or less satisfactory to explain the fact but they will remain mere hypotheses, for the original discoverers of special language are unknown. The practice of distinct language in the special professional work might be discovered once or more than once and spread over various groups. In this spreading among different groups it may be explained by different reasons. Let us suppose that amongst some groups it was due to the fear of spirits which might interfere with the economic activity of the hunter if the animals, implements and arms are named by their names. Since it was found that the non-naming brings «luck» in hunting the other groups naturally might imitate the discoverer, especially if the change of language did not present great difficulties and especially if such a new language became a source of interesting experiments and distraction, a case which is actually observed. If the ethnographer would insist upon the reason, the questioned hunter might reply, as the Tungus do, — «there will be no luck in hunting», or «the spirits so and so must not know about it», or even «the animal must not know it» etc. My experiments with the Tungus convinced me in fact that they may give various reasons when they are pressed, especially if the answer is already included in the question, which is the usual way of getting data. But if one does not press them they simply reply «such is our custom», or «such is the regulation of hunting» [156]. As a matter of fact in an average case a Tungus does not bother himself with the question as to why he uses these customs and he does not need their justification.

* * *

According to the Tungus statement in former times they did not hunt the TIGER and at the present time many of them still abstain. The reason given is that the tiger is the same as bajanam'i — the taiga spirit (cf. infra). However, this is not a prohibition, and it may be a simple justification of their attitude of fear conditioned by the actual danger which may result from the hunting the tiger. Yet, the tiger is considered as a good-natured animal too, which is seen e.g. in the fact that the tiger always brings food to its young [157].

The cleverness of the tiger is also seen in its very good knowledge of the habits and possibility of hunting other animals. The Tungus suppose, I think with a good reason, that the tiger knows that alone it cannot fight a big bear, which sometimes takes the tiger's spoil; it knows that it cannot attack the wild adult bear unless the latter is surprised in a sleeping state; it also knows that it cannot fight man when the latter is armed; and it does this only in the case of being very hungry or excited and frightened, i.e. when it becomes «stupid».

About the same complex of ceremonialism as with the bear is found when the tiger is killed. However, this complex is not as rich as that connected with the bear. Indeed, here it ought to be considered that the geographical distribution of tigers is rather limited, and this animal is known only to the Tungus of Manchuria, chiefly amongst the Birarchen (vide SONT). The Tungus hunt the tiger for it is a rather valuable animal for its skin, its bones used as Chinese materia medica, even its moustaches used for teeth cleaning etc. However, the Tungus are very sceptical as to the medical effects of the bones. When they happen to eat tiger they do not like its meat which is hard and sour to taste. Although among the Tungus the tiger is not surrounded by special prohibitions, these spread owing partly to the same condition as that with the bear, and partly to the alien influence. In fact, lately amongst the Manchus the using of rugs made of tiger's skin has developed into a prohibition. At a certain moment the tiger's skin as a seat became a privilege of high officials (amban), and the Tungus of Manchuria obeyed their superiors of the military organization and the prohibition came into the existence. However, the Tungus themselves believe that there is no prejudice in using tiger's skin as a seat and treat this custom as a «Manchu law». Naturally with the complex mythology and stories found in the Chinese books the meaning of this prohibition may grow still further and become justified by new considerations. I think this is the case of the Goldi and their neighbours who fell under the Manchu-Chinese influence earlier than other groups. Amongst the Tungus of Manchuria the women must abstain from eating tiger meat.

The folkloristic aspect does not now concern us, So I will leave this question to my further publications. Among the Tungus groups the tiger is called by different names. It is called bojuja (Ner. Barg.) but it is very little known amongst these groups (vide SONT); lavu (Kum), lawda (Bir.) which according to the Tungus, is borrowed from the Chinese; m'er'ir'in (Bir.) — «stripped»; ngalaja (Bir.) — «fear exciting»; tasiya (Khin.) — from Manchu tasxa; utaci (Bir.) (e.g. in combination m'er'ir'in utaci) — «one who has children» (great father, father); yet it may be called merely amba (Goldi and their neighbours) - «great», also by honorable terms like that used for «bear», e.g. mafa (cf. Manchu term), ama etc.. So in the terms used for the tiger we may see the same phenomenon as in the case of the bear, so I do not need to repeat what has been stated in reference to the terminology.

Regarding the.family life of the tigers the Tungus information is not complete; amongst the Tungus of Transbaikalia it is very poor.

Among the little known animals, the leopard may be

mentioned as one which, according to the Tungus, is very intelligent. It is

called either «the beast» — bojuja (Khin.) or by a special term, — megdu

(Khin), muyan jarya (Manchu Sp.).

Domesticated Animals

Domesticated animals interest the Tungus. The REINDEER is considered as a very intelligent animal. Its intelligence is seen by the Tungus of Transbaikalia and Reindeer Tungus of Manchuria in the whole complex of relations which have been established between man and reindeer. The Tungus recognize cleverness of this animal which they see in the fact that the reindeer obeys the human voice, knows many commanding words, also their personal names given by the Tungus, carefully behaves when carrying loaded bags arid especially children in their cradles, knows how to defend itself against wolves and knows that the best protection for it is the human beings, to whom it runs when in danger and whenever possible. The Tungus recognize that the reindeer possesses a soul which may exteriorate like that of man and other animals, and a mentality which is not, however, equal to that of man; at last, according to the Tungus, the reindeer does understand the change of mood in man, as do e.g. the dogs. The intimacy of relations makes the Tungus love the reindeer nearly as human members of the family and when a Tungus is alone he may talk to the reindeer which, according to the Tungus, can understand. Again, this understanding of man can be admitted not too literally, but about in the same manner as we have seen in the case of the tiger. However, with the supposition that the reindeer may become a placing for spirits, the Tungus may address his speech to the reindeer in view of speaking to the spirits which naturally can understand human speech. Naturally the Tungus are very familiar with the behavior of the reindeer during different periods of their life. When they are left in the herd the functions of the male as protector of the herd are interpreted by the Tungus as one of the manifestations of the reindeer intelligence. The same is true also of horses which in the herd show still better organization, especially when they are attacked by the wolves and when females form a circle turning their heads toward the center where the colts are grouped and their strong back legs outside, and when the stallion is running round the formed circle and is the first to maintain order and to meet the attacking wolves. The Tungus know very well the behavior of the female reindeer towards the males at different periods, also towards the fawns. So the Tungus recognize the feeling of love for the young and in this respect they say that there is no great difference between the reindeer and man. Such an inference is naturally made as a result of long observation of the life of this animal, which the Tungus must know if they want to be successful in breeding. Thus, the Tungus idea is that the reindeer is very intelligent and is frequently used by the spirits. In further discussion I shall come back to the problem of the reindeer function in the rites and ceremonies, also in the shamanism.

DOGS are considered as very intelligent animals too. This opinion is shared by all. Tungus, but not in reference to all dogs. As regards the mentality of the dogs, the Tungus infer from the observation of this animal, as seen e.g. in the fact that, within certain limits, the dogs can understand human speech, particularly simple sentences and their own names; they can understand the change of mood in man, as is also true, according to the Tungus, of the reindeer; they know their right on the campment when, for instance, they do not touch the hunting spoil or food left without men in the wigwam, but take possession of food reserved for them; the dogs know their functions in the reindeer breeding and watching the campment and the herd; the dogs in case of danger look for protection from man; dogs are specialized in their functions, e.g. for different kinds of hunting in which the dog actually cooperates with man. The high mentality of the dog is also seen in the fact of storing food if it cannot be consumed by the dog (especially females). Naturally the dogs possess souls, as reindeer do. However, dogs as a rule are not eaten by the Tungus, the reason being that their meat is not good, especially at old age, while, the dog is more valuable forwatching, hunting and simple companionship (e.g. the man must treat the dog like his companion in hunting giving the dog a good portion of the hunting booty, etc.). The dog plays a very unimportant part in the ritual complex and its part in the folklore is rather limited. Indeed, this attitude towards the dog has no reason in so far as the Tungus idea about the mentality of the dog is concerned. I shall return to this question later. Naturally, the Tungus distinguish between intelligent and non-intelligent dogs as they do in reference to other animals.

The Tungus recognize a certain mental ability in HORSES. However, their knowledge of this animal, even amongst the Tungus who have no other riding or draught animals, is much inferior to that of the reindeer. The Tungus also recognize that the horse has soul, individual character and varied mental ability. So they say that there are clever horses which after getting experience know conditions of taiga and do not waste their energy on useless jumping, unreasonable fear etc. These horses spare their energy, eat the berries, hydrophites etc. Such a horse can be used for two or three weeks even during the season when the usual food is not available for the horse [158]. However, the mentality of the horse is inferior to that of the dog. CATTLE, the cows and oxen, in reference to their mentality are put by the Tungus as inferior in the scale. However, the Tungus do not know these animals as they know the reindeer and dog. Some facts of interest, as for instance, the reaction of these animals on slaughtering, are noticed by the Tungus, — when doing it (e.g. amongst the Nomad Tungus, also amongst the Tungus formerly reindeer breeders in the Nerchinsk group) usually send the cattle away as far as possible [159]. The same preventive measures are taken when reindeer are slaughtered. The explanation given by the Tungus is that the animals do not like — to see how one of them is slaughtered [160].

* * *

In reference to the Tungus knowledge of animal psychomental complex amongst the animals which are not dangerous for man and which are not domesticated, the first places are occupied by the CERVINES and fur bearing animals, which the Tungus must know for their hunting.

The Tungus collect and transmit from generation to generation the facts regarding animals mentality and psychology, so that at last the body of facts becomes enormous and the conclusions are rather good. In most of the animals the Tungus recognize certain mental power, which however is not the same in different animals as we have already seen before. The Tungus do not believe the cervines, such as the elk, Cervus Elaphus, reindeer, and musk-deer to be clever animals and they recognize in addition that these animals may be intelligent and stupid individually. The Tungus (Biracen) quoted to me an evident instance of the stupidity in animals. A Tungus on horseback approached a male reindeer. Instead of running, the animal looked and went slowly round the horse. The animal was naturally killed. Such a stupidity, according to the Tungus, is rare. However, they know rather well the character and degree of the attention, development of smell auditory, and visual power. According to the Tungus these animals know how dangerous man is and they run away from him as soon as they can smell, see or hear him. Amongst the Tungus of Manchuria hunting on the roe-deer is very often practiced by hiding under a special dress made of roe-deer skin, so that the skin from the head of the animal together with the small antlers is put on the hunter's head. The roe-deer allows the hunter to approach the herd of roe-deer to within a short distance if the wind does not bring the human smell to which all animals are very sensitive. The hunter may then easily kill the animal [161]. On the same knowledge of animal psychology there is also based the hunting of the Cervus Elaphus challenged by the hunter by imitation of male's voice calling him to fight. The imitation is perfect [162]. In the same way the Tungus exploit the maternal feeling of the female roe-deer and musk-deer to attract them near to the hunter by imitating the cry of the fawns (only during the period when the fawns are small).

The Tungus names of these animals show some interesting features which may be pointed out as characteristic of the Tungus psychomental complex. We have seen that in their classification the Tungus give no hints as to the mystical and supernatural character of these animals. Their terminology is a pure and simple zoological and industrial specification of the animals. Again if these animals may become particularly powerful, more powerful than man, it is due to the spirits which may locate or place themselves in these animals. Here it may be noted that the Tungus very often say that some animals are good and bad, even clever or stupid, intelligent and unintelligent which is misunderstood by, the travelers and then a very mystic interpretation is given. For instance, the animal which does not allow itself to be killed, runs away etc. is called stupid etc., but in the Tungus complex this does not mean to say that the animal individually taken is stupid; it is «stupid» for the hunter who cannot kill it. Therefore sometimes the Tungus say that a «good animal», «clever animal» goes straight under the hunter's shot, or in the hunter's trap, while a «bad» «stupid» animal does not. It is a judgment from the point of view of Tungus aim of hunting, but they have no such a term like «difficult to be hunted» or «easy to be hunted». So that when the Tungus say about squirrels that they are «clever» and «like» the hunter it does not mean, as it is interpreted, that they want to be killed by the hunter in order to be pleasant to him. It is one of those metaphors in which all languages are rich. However, since the souls of these animals may be influenced by the human soul, — direct or through the intervention of other spirits, — there may be a certain evaluation as to the animals' soul, and this may become again a source of a misleading inference regarding the mysterious character of the animal psychology and mentality.

* * *

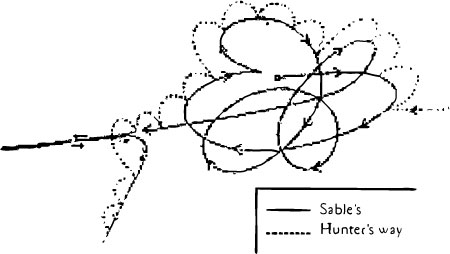

The Tungus consider the SABLE (Mustela zibellina) to be a very clever animal which is not easily taken. The method of misleading the hunter practiced by this animal is quoted (by the Birarchen) as one which I will now give in detail. When the sable wants to leave the night shelter it does not leave it at once but by making several loops (from thirty metres to two kilometres) and returning to his starting point, after which he runs straight to the new place. If the hunter does not know this behavior of the sable and follows the foot prints of the animal he will spend many days and perhaps will not be able to find the actual direction of the animal. Yet sometimes the hunter loses his mind. Therefore the Tungus use a simple rule: never cross the sable's single track while the fresh double track can be crossed which is shown in the figure.

In connection with this it may be noted that the Tungus know very well, and professionally they must know, the character and meaning of the tracks of different animals. For instance, the bear usually makes two parallel tracks in opposite directions, so that it is difficult to know the actual direction in which the bear has gone. The steps must be counted. The horse goes a long way during every night so that finding it is difficult. All mustelidae leave the same type of tracks, as the sable.

Amongst the Tungus there is a strong conviction that animals sometimes commit suicide. There is a small bird which puts its neck in between two narrow branches of shrubs and trees and suffocates; the same is observed amongst the forest mice. The analysis of the situation convinces the Tungus that there is no purpose of protruding the head between the branches, so that the cases are regarded as suicide. The «old men» used to say that the animals did this because of missing the sunrise, which interpretation is undoubtedly connected with a complex of folklore. These case are often observed. As to other animals the Tungus know of no cases. The cannibalism of the salmon, in the autumn in the small rivers, when the teeth overgrow in old fishes (five years old, the last year of the cycles) is considered as having the purpose of destruction, for otherwise the fishes which do not die in this way will die owing to the destruction of their bodies by a kind of worm.

The WILD BOAR is considered as the strongest animal, which possesses a certain intelligence and a very strong sense of smell but is defective in some respects, e.g. it sight is not good and it cannot easily change direction when running. The intelligence of this animal is seen, for instance, in the method of fighting the tiger [163]. The mother's feelings as a sign of high intelligence are seen by the Tungus in the wild boar when the female accumulates leaves, dry grass, small branches and other material into a heap, goes under it and by turning herself round forms a nest with an entrance in which she gives birth to the young well protected against mosquitoes and midges.

* * *

Yet the Tungus do not deny certain intelligence of the BIRDS. I had occasion to relate the way of co-operation between the hunter and raven, when the raven from its high position notices the animals and flying in their direction leads the hunter forward. As soon as the animal is killed the raven receives the bowels and intestines as a natural compensation. According to the Tungus (Birarchen), the raven would pay no attention to them if they go out without the rifle or with a stick instead of the rifle [164]. Yet the ravens usually express their emotion, when the animal is killed, by a cry and «dance» around the hunter when he skins the animal. As a matter of fact, the Tungus do not understand the mechanism of this co-operation and many of them refuse to believe that the ravens may bring «luck». Should the man not believe and fail to follow the raven, the raven would not show the way [165].

The eagle is considered by some Tungus as a stupid bird. They are inclined to see this manifested in the over eating of the eagle when it may have its prey. Yet, according to the Tungus, the eagle's stupidity may also beseen in the fact that when it attacks the roe-deer it pounces on the back of the roe-deer which runs in the forest. The eagle tries to stop the animal by grasping a tree with one leg. The leg is sometimes broken off and the eagle perishes [166]. The Tungus see the cleverness of the cuckoo in the fact that they observe the migration of this bird on the back of the large goose. The birds' languages are also known to the Tungus who sometimes may understand what the various cries of birds «mean». Naturally, the birds-imitators, like some thrushes, are greatly admired, but the Tungus know perfectly well that these imitators do not always «knew» the meaning of imitated words and phrases.

I will not quote other facts of this group of my observations. The facts here quoted may suffice for showing that the judgment of the Tungus regarding mental and psychic characters of the birds is also based upon the observation of the behavior of the birds which the Tungus first describe, and after which they draw conclusions and if necessary give names to the birds many of which, it is true, are onomatopoetic. I will abstain from the linguistic analysis of these names which may be used as good basis for making up the idea of the Tungus conceptions regarding birds in general. However, such an operation is extremely dangerous for those who are not familiar with the language and psychomental complex of the ethnical groups discussed. Since this method will not bring too many new facts I will not give my analysis which may be disastrously imitated by other writers on this subject.

I have not recorded any facts or opinions regarding the snakes, frogs, toads, turtles and lizards. These animals are known to the Tungus chiefly from the alien folklore, while their idea as to the mosquitoes, gad flies and midges is not very high. However, the Tungus also recognize that some INSECTS possess some mental ability. So, for instance, the Tungus believe that the ants are clever, and perhaps for this reason they do not like to destroy the constructions of the ants and do not want to deprive them of their «houses» (i.e. flowers, vide supra Section 22). The wasps are also considered as clever animals.

The insects fight between themselves. For instance, the drones attack the gad flies. They perforate the abdomen and suck the liquid contained in the heart which is «like sugar». The drone steals the honey from other insects. In order to see the behavior of the insects the Tungus make them fight, e.g. wasps and spiders. The spider's bite is considered very poisonous for man, while that of wasp is only painful [167]. When the spider attacks other insects it seizes their with «arms» and covers them with a network. Two spiders are believed to be very fierce. If one puts even a large spider into the web of a small spider the owner will attack and the large spider will fall down from the web in order to leave the field. The reason is that a spider does not go to the web belonging to another spider. The spider is «fishing» when it examines the string by touching it with the «arm» in order to see whether there is any booty or not in the net. If the string is heavy then the spider pulls it up to catch the booty. The ants preserve their eggs deep in the earth, protecting them against the frost. Ants fight with other groups of ants, maintain the same roads and repair very quickly the damages in their constructions.

* * *

This description of the Tungus ideas regarding the psychology and mentality of animals might be increased with a great number of facts taken from the folklore. As I have already pointed out I do not want to do this, for in the eyes of the Tungus the folklore is not the source of exact knowledge and the Tungus, when they need facts are not inclined to use the folklore as a source of information or references. The information gathered by the Tungus from other ethnical groups (e.g. the Chinese, Manchus, Dahurs and Russians) is not rejected by the Tungus but it is also not blindly adopted. It may be very often heard from all other groups that the Tungus knowledge of the local animals is superior and that the Tungus are critical. In fact they spread this scepticism even with regard to the animals unknown in their territory. However, this does not mean that the Tungus do not reproduce in their folklore stories which are not believed by them to be «true».

If we summarize what has been expounded in the present section, we may say that the Tungus as observers do recognize certain psychomental characters in the animals. This description of the Tungus opinion regarding the mentality of the animals is near to that given by Sir J. G. Frazer (cf. The Golden Bough, Part V, vol. 11, p. 310).

«It has been shown that the sharp line of demarcation which we draw between mankind and lower animals does not exist for the savage. To him many of the other animals appear as his equals or even his superiors, not merely in brute force but in intelligence» [168].

Indeed, it is not exactly what may be formulated in reference to various groups. It is safer to say that the ethnical groups of non-European complex in reference to some animals admit their physical and in some respects their mental superiority, which is conditioned by their experience and adoption of certain theories. The idea of Sir J. Frazer is however deeper, namely, he proves with all his work that the «primitive man» is oppressed by this superiority and spirits which people the man's environment, while he, Sir J. Frazer, is free from this belief. This complex of superiority becomes one of the important causes of misinterpretation of the animal mentality, common even amongst those who have devoted themselves to the study of animals, and being the fundamental characteristic of the low class of city dwellers who do not know the animals and are convinced of their own immeasurable superiority, even as compared with the villagers. L. Sternberg who followed the ideas and method (i.e. picking up of facts and making of them mosaic pictures) of Sir J. Frazer has gone still further when he asserts that «the animals…are pictured as perfectly human — like beings as to their physical nature and mode of life, but who like at the same time to appear to man in forms of one or another animal» (Gilak Folklore p. XIV). This inference is made chiefly from the folklore in which, according to this author, «the Gilaks do not see the product of imagination but real events», for they take for real the facts, that which seems to be facts, the dreams and hallucinations (I.e.). This statement cannot be accepted tinder any conditions for if such be the Gilak he could not survive under the pressure of this psychosis. This picture of the Gilaks is done with the colors more vivid than those used for the same subject by Sir J. Frazer, e.g. in the following broad generalization: «The speaker imagines himself to be overheard and understood by spirits, or animals, or other beings whom his fancy endows with human intelligence; and hence he avoids certain words and substitutes others in their stead, either from a desire to soothe and propitiate these beings by speaking well of them, or from a dread that they may understand his speech and know what he is about, when he happens to be engaged in that which, if they knew of it, would incite their anger or their fear.» (Op. cit. Part II, pp. 416 — 417). And furthermore »… man's first endeavour apparently is by quietness and silence to escape the notice of the beings whom he dreads; but if that cannot be, he puts the best face he can on the matter by dissembling his foul designs under a fair exterior, by flattering the creatures whom he proposes to betray, and by so guarding his lips, that though his dark, ambiguous words are understood well enough by his followers, they are wholly unintelligible to his victims» (ib. pp. 417-418).

As a matter of fact this picture may be referred to a schizophrenic who is affected to the last degree of mania of persecution. These are artistical images, but they are not reality. There are two sources of these creative achievements; first, the complex of superiority which guides the writer, and second, an artificial selection of facts taken out of the complexes in their formal aspects (very often misunderstood and badly rendered) so to say functionless. What happens with such authors is that they concentrate the facts gathered amongst several persons and refer them to an ideal «Gilak» or «primitive man» which never existed and never was thinking as they make him seem to do. The method of gathering facts from diverse ethnical groups and their concentration is still more productive of strongly expressed images. In order to make the picture still more expressive the complex as a whole is not given, but there are selected those facts which may particularly impress the reader affected by the same complex of superiority and avidity for reading a «real», but frightening story, the reader whose psychomental complex cannot be any more satisfied with the detective stories and cinematographic melodrama. In addition such a picture of primitive man gives a moral justification of his psychical destruction, or ethnical absorption. Ethnologically, these creations are a very rough product of modern ethnocentrism. I will not here speak of the technique of this class of work which actually can good carried out even with no great personal effort, — by assistants who read, and put facts on the cards and make a card catalogue. It shows still better the modern type of serial manufacturing.

I do not need here to bring forward the ideas of the writers like Levy-Bruhl and his numerous followers. From the description of the Tungus knowledge and methods of observation we have seen that the process of mental work does not differ from that of any other observers of natural phenomena, if the observers need to have an exact idea as to the phenomena observed. In this respect their method gives more security of scientific proceeding than that of Levy-Bruhl who bases himself chiefly on selected facts and whose aim is to prove (justify) certain preexisting assumptions without worrying about the disastrous effects of such a work. Indeed, the disastrous effects do not spread very far and they do not affect those of his readers who have practically to deal with the groups of non-parisian complex. Their effects sterilize only those young men who follow the ideas and methodology of their leader, which fact perhaps has only personal importance.

149. As a matter of fact, even European scientific terminology is not free of enigmatic expressions borrowed from those old conceptions in which the hypothetic spiritual factor occupied an important place. Most of controversies regarding teleologism, vitalism etc. are based on the poverty of terminology and its ambiguity due to the semantic extensions and variations.

150. The experiments of the domestication of wild animals is very clearly connected with these experiments. I shall return to this question.

151. The fairy stories concerning animals form a special branch of folklore, but every Tungus knows that these are fairy stories, and not the facts.

152. According to the Birarchen bears, elk and the Cervus Elaphus without antlers are not clever, while the Cervus Elaphus with the antlers and tigers are very clever. The elk and bear recognize man's presence by his smell. The tiger has perfect sight, hearing and sense of smell. However, it runs rather badly. The bear is a perfect runner, which is never tired. The sight is very good in the raven and wolf. The wild bear has poor sight, so he can see only on a short distance, but his sense of smell and hearing are very good.

153. Cf. D. K. Zelenin, Taboo etc. p. 10.

154. As it will be later shown the term galegda has still greater use, namely, it may be referred to the localities and things touched by certain spirits. It must not be, however, inferred that in this term and behavior of bears and tigers as described, there is some thing connected with the «religious» conceptions.

155. However, among the Birarchen the women are now allowed the posterior part of the bear.

156. The same reply would be received from any European when he is asked for the reasons of prohibition of terms for sexual organs. Perhaps if he is pressed still further he may give some moral justification to the existing prohibition. Moreover, it must be considered that the so called primitive peoples do possess certain conceptions of social politeness which implies satisfaction of the questioner, especially one of a superior ethnical group, and under the insistence on the part of an influential group well equipped with arms and power, even sometimes soldiers, foreigners; they would not dare to resist in their mutism, — if they have nothing to say they would find any handy explanation. So there must be used evidences checked up by cross examinations, and the place of folklore in this matter must be very modest. Yet, every evidence must be taken in its relative complex meaning.

157. It ought to be pointed out that the Tungus inference regarding parental feelings needs perhaps some correction. An a matter of fact, young bears have a different kind of food as compared with the tigers and in the given description we have the booty consisting of meat.

158. The case of accustoming the horse to eat meat (SONT p. 39) is considered as a product of human cleverness.

I do not make reference to the opinions of the Reindeer Tungus who are sometimes familiar with the horse, but since they do not like it their opinion may be influenced by their hostility towards this animal.

159. Once in 1912 in the Tungus village Akima (Nerchinsk district) I observed a kind of «rebellion» of cows and oxen when one of them was slaughtered before their eyes. This case gave me a good occasion for carrying out an interesting observation as to the Tungus ideas on this matter and methods of preventing «rebellions». Let us remark that the fact of non-reaction amongst the animals as observed in slaughter houses perhaps needs some additional verification. The seeming lack of reaction expressed in the docility, is also observed in men when they are slaughtered in a large number, as it is observed among the civilized nations during the revolutions when the changing parties slaughter each other. The penetration into the animal psychology is greatly hindered by the fact of lacking speech in domesticated animals, very limited knowledge of animal psychology in general, and repulsive reaction of «seeing» on the part of those who are connected with the profession of slaughtering.

160. If these observations of the Tungus are correct, the case of human sacrifice, and cannibalism for which the populations practicing them have no aversion, as well as the cases of public capital punishment ought to be understood as peculiar cases of the adaptation of human (ethnic) psychology to the special conditions in which the complex of «religious ideas», as well as «social ethics» take special forms, and the practice becomes a common phenomenon.

161. Naturally this method is well known amongst other hunters e.g. the Bushmen who simulate the ostrich. Perhaps the quaternary painters did represent such a hunter, who has become known, chiefly as «magician» and even «shaman».

162. The horn is made of a wooden piece of birch bark and it was known centuries ago (vide SONT) which is indicative that this practice is very old. It may be noted here that, according to the Tungus of Manchuria, the tiger also knows this method, but the tiger cannot exactly reproduce the last note (cf. E. Shirokogoroff, Folk Music No. 38) so that the hunter may recognize whether it is a cry of deer or a tiger' imitation. This fact is also quoted by the Tungus of Manchuria as showing a great mental ability of the tiger.

163. Here I want to relate a case which has been quoted by the Tungus for showing the mentality of this animal. An old and strong boar was chased by three tigers. The tigers were weak, perhaps, already starved which sometimes happens with them, and which was later confirmed by the examination of their bodies. The hunter followed the boar and the tigers for seeing what would happen to them. At a certain moment in a place good for fighting the boar stopped in such a position that it was with its back to the tigers but it could see them. It was attacked by one of them. The boar in a second changed its position and cut the abdomen of the tiger, when the latter approached at a short distance; when the tiger was killed the boar occupied its former position and showed that it wanted to continue on its way. The second and third tiger subsequently attacked the boar and both of them were killed in the same way. Then the boar changed its behavior and carelessly considered the dead bodies of its enemies. At that moment the hunter killed the boar so he brought back four big animals.

164. They say the same of the crow.

165. Such a case of co-operation between the hunter and raven may be easily understood, but the Tungus are inclined to see in it something different. They go even so far with their hypotheses that they suppose that this bird may predict. The Tungus reasoning may be seen from the given example below. «There was a company of seven with 13 horses (going for hunting). One of horses was very weak (sick). The raven cried at the moment of their leaving. The owner of the bad horse killed (an animal). The raven again cried. The next night one of the good horses perished in the marshes. The sick horse became well.» The interpretation is that the raven predicted the success in the hunting and recovery of the horse. However, not all Tungus would agree with such an interpretation, and the reasoning based on simple post hoc propter hoc will not satisfy them.

166. The Tungus hunt the eagle for selling the feathers to the Chinese. When they abstain from killing it the reason is that the Tungus do not need it, while useless killing is not practiced as a rule.

167. For the bears; who like the honey the sting of good is not effective. The same is true for some people.

168. Here, Sir J. G. Frazer's opinion as to his scientific ideas and superstitions of savages is of interest He says: «For whereas the order on which magic reckons is merely an extension, by false analogy, of the order in which ideas present themselves to our minds, the order laid down by science is derived from patient and exact observation of the phenomena themselves» (op. cit: Part VII, Vol. II, pp. 306). However, he comes to a somewhat pessimistic conclusion as to his science by formulating: «We must remember that at bottom the generalizations of science or, in common parlance, the laws of nature are merely hypotheses»… and «In the last analysis magic, religion, and science are nothing but theories of thought» (ib. p. 306). I do not need to especially stress that «the sharp line of demarcation» never was a hypothesis advanced by science, but it was one of elements of extension, by false analogy, of an ethnocentric and anthropocentric behavior.