31. Aspiration and Bilabialization of the Initial Vowels a Phonetic Fashion

31. Aspiration and Bilabialization of the Initial Vowels a Phonetic Fashion

In the work of A. Sauvageot, one of the most important evidences in favour of the common origin of the Ural-Altaic languages is the phenomenon of the occurrence of initial bilabial consonants by the side of aspirated and non-aspirated vowels, also by side of glottal consonants. Similar facts have been observed in many linguistical groups, so this phenomenon is not characteristic of the languages called Ural-Altaic. So, for instance, N. Matsumoto, in his paralles, has shown a great number of instances where 0, h, x, f, and p are met with in the same words (stems) of different dialects of the Austro-Asiatic group. The Chinese dialects reveal the same picture.

Yet the Indo-European languages know this phenomenon as well. In the Tungus languages this phenomenon was noticed by A. Schiefner, L. Adam, and W. Grube, and was extended to the Mongol and the Turk by P. P. Schmidt [72]; but all of them did not go so far as G. Ramstedt, who supposed this phenomenon to have been a consequence of the transition from the bilabial spirant to the aspiration and zero, as p>h>0. A. Sauvageot has called this hypothesis «la loi de Ramstedt.» Further considerations have made P. Pelliot suggest, instead of a spirant bilabial, a bilabial occlusive *p [73] Indeed, it is only hypothesis backed by the presumption of the common origin of the Ural-Altaic languages, and in this respect it may be regarded as its by-product. In its formulation by G. Ramstedt, we have, perhaps, a case of mere «reasoning by analogy,» implied by. this hypothesis [74]. Although in the Indo-European languages the loss of the initial labial tenuis spirant has been

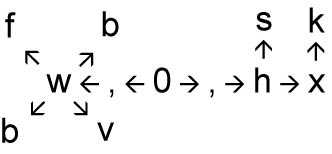

recognized as an important moment in the formation of Armenian and Celtic, however, there has also been, for instance, in Latin, the «consonantic reinforcement» of u>v, which is included by A. Meillet in the class of «accidents particuliers»[75] as being in conflict with the above-mentioned «loss.» I do not know whether the «loss» is a fact or a hypothesis, but the Latin «accident» is very instructive I have made [76] a different approach to the same problem in Tungus by pointing out the existence of certain phonetic fashions which I have designated as the «aspiration» and the «bilabialization» of the initial vowels. The increase of incursion and emphasis may result, as they actually do in living dialects, in the formation of bilabial, labio-dental, and glottal consonants, both tenues and media lenes, also both spirant and occlusive. So the scheme of variations is of the type shown in the accompanying table. Here the original sounds subject to variations are vowels and not consonants. Since these variations of sound may now be observed in working, as I have observed them in different Tungus dialects, I think the hypothesis of G. Ramstedt is quite unnecessary for the interpretation of the occurrence of 0, h, x, p, and f in Tungus and Mongol. The situation is complicated by the fact that similar variations are not universal; that is, there are cases when the parallelism is not complete at all. Another fact is that similar variations are known in other languages in which these variations may be due to different causes, including actual loss; also, as is observed in the Tungus, they may be due to the increase through the aspiration and the bilabialization of vowels. Owing to this, I cannot agree with A. Sauvageot's definition of G. Ramstedt's hypothesis as a well-established historic-phonetic law [77].

Since the above-discussed hypothesis has already been promoted to the grade of law and put at the basis of the hypothesis of common origin of the Altaic languages and, furthermore, the Ural-Altaic languages, I shall, in addition to my former papers, bring forth some new facts and considerations, first in the field of Tungus languages.

In Tungus languages I have distinguished two phonetic movements and I have shown that the Southern Tungus, as represented by Manchu, is inclined to bilabialization, while the Northern Tungus is inclined, at least in some dialects, to aspiration. These are two distinct characters of two phonetic complexes correlated, shall I add by the way, with a complex of other phonetic peculiarities, as, for instance, the different behaviour in the palatalization of consonants, the transition to alveo-dental spirants, etc. Besides these two groups, we know several dialects which possess neither aspiration nor bilabialization of vowels. This phenomenon affects different stems too. I shall now give some instances.

1. Aspiration is found in the Goldi, while zero is found in the Northern Tungus and Manchu Writ.; and slight bilabialization in Manchu Sp.

a. xagdu, hagdu (Goldi, Grube), agdun (Bir.), ukdun (Manchu Writ.), wugdun (Manchu Sp.)—«the pit dwelling» [78]; cf. agdun (RTM, Bir.)—«the bear's haunt»; corr. avdun (Khin., Ner.) (Irk. Tit.) in the same sense.

b. hoskta. (Goldi, Grube), osekta (Bir.), osikta (Mank.), osikta (Ner.), usixa (Manchu Writ.), wuziya (Manchu Sp.)—«the star.»

c. xujun (Goldi, Grube), ujun (Turn., Lam.), ujun (Manchu Writ.), wujun (Manchu Sp.)—«nine.» [79]

2. Aspiration is found in Goldi and some Northern Tungus dialects; zero, in Manchu Writ, and Manchu Sp.

a. ximana (Goldi, Grube), hemanda (Turn.), imanda (Khin.), emanda (Barg., Ner.), emana (Bir., Kum.), etc. nimangi (Manchu Writ.) [yih-ma-kih (Nuich. Grube)]—«the snow.»

b. xupi (Goldi, Grube), ovi (Bir., Khin., Ner., Barg., RTM), ovi (Neg., Sch.), efimbi (Manchu Writ.) evimbe (Manchu Sp.)—«to play.»

c. xyrre (Goldi, Grube), ereki (Bir.), etc., erxi (Manchu Writ.), erye (Manchu Sp.)—«the frog.»

3. Aspiration is found in Goldi; aspiration and zero, in Northern Tungus; bilabialization, in Manchu.

xukte (Goldi, Grube), ikta (Bir., Kum., Khin., Ner., Barg., Mank.), veixe (Manchu Writ.), veye (Manchu Sp.).—«the tooth.»

4. Zero is found in Goldi, Northern Tungus, and Manchu Writ.; bilabialization, in Manchu Sp.

olg'e (Goldi, Grube), ulg'an (Bir.), ulg'an (Manchu Writ.), wulgjan (Manchu Sp.) [cf. wuh-li-yen (Nuich. Grube)]— «the pig.»

5. Zero is found in Goldi and Northern Tungus; bilabialization, in Manchu.

iga (Goldi, Grube), irga (Ner., Barg., Bir., Kum., Mank., RTM), fexi (Manchu Writ.) [80]— «the brain.»

6. Zero is found in Goldi; aspiration, in Northern Tungus; zero, in Manchu.

ori (Ol. Sch.), xeuri (Tum.), ergembi (Manchu Writ.) —«to take a breath.»

The instances of these six combinations may be increased, almost ad libitum, especially in the cases where Goldi has aspiration. The conclusions which may be safely drawn from these facts are — (1) Goldi is a language where the aspiration is known; (2) the words bilabialized in Manchu do not always have the initial p in Goldi, and they can be both aspirated and non-aspirated; (3) the words not bilabialized in Manchu may be found to be aspirated in Goldi; (4) the words aspirated in Goldi may be found aspirated and non-aspirated in Northern Tungus and bilabialized and non-bilabialized in Manchu.

Let us now proceed to the initial p and other labial consonants in Goldi and other languages. Since these examples are known from other publications I will not give instances here.

1. Goldi p may correspond to the Manchu f in words unknown in Northern Tungus and refer chiefly to the Manchu cultural phenomena (about one third).

2. Goldi p may correspond to the Manchu f in words known in Northern Tungus with the initial aspiration or zero (more than one third).

3. Goldi p may correspond to the aspiration in Northern Tungus (only five cases known by me).

4. Goldi p may correspond to the Manchu b (I have noticed only two cases).

5. Goldi f sometimes corresponds to the Manchu f and usually to Goldi doublets with p and the same meaning (very rare cases).

6. Goldi w and v may correspond in rare cases to the Manchu v and f, to the Goldi u (in doublets) and different sounds in Northern Tungus dialects, e.g., ng, b, especially in words unknown in Northern Tungus and designating local terms.

7. Goldi b may correspond to the Manchu and Northern Tungus b;it occurs frequently so that there are only a few exceptions corresponding to other sounds in Manchu and other Tungus dialects; in Manchu the initial b is almost voiceless.

These series of facts allow us to generalize: (1) the Goldi language shows a definite inclination to tenues bilabial occlusive (p) occurring in cases where it is met in Manchu with spirant / and in rare cases b

corresponding to the Manchu Sp. p; (2) the Goldi p in a limited number of cases corresponds to the aspiration and zero in the Northern Tungus dialects; (3) the Goldi p in a great number of cases corresponds to the Manchu / and to the Northern Tungus aspiration and zero; (4) the Goldi / is rare and is never met with in words common only to the Northern Tungus, but it is met with in words in Manchu found with /, and sometimes in Goldi with p (doublets); (5) the Goldi w and v; are rare and correspond to the Manchu w, v, and f, also the Goldi u (bilatialization in doublets); (6) the Goldi b is met with as frequently as in other Northern Tungus dialects and in Manchu Writ.

The reaction of the. Northern Tungus dialects is such that they alter the initial / of foreign words into p, for the initial / does not exist in the Northern Tungus dialects with the exception of cases like that of the Birarchen dialect where I find three words, all borrowed from Manchu, with the initial f. However, in this form they are used only by persons familiar with the Manchu phonetic peculiarities.

It should be pointed out that the process of bilabialization of the initial vowels is a phenomenon observed in foreign words with the initial vowels borrowed by the Manchus. By the bilabialization are affected first the words with the labialized vowels. Yet the Manchu Sp. is more bilabialized than the Manchu Writ. In fact, all u's and the greatest part of the o's of the Manchu Writ, in Manchu spoken are strongly «bilabialized.» That the process of bilabialization is not a very recent phenomenon one may see from the instances of Nuichen and several evidences of formation of new labial and bilabial consonants from the labialized and even non-labialized vowels. Of course, one may reject the last series of facts by explaining them as a result of the loss of consonants, but the fact of recent bilabialization (Manchu Writ, and Sp.) of foreign words and the fact of the process of further bilabialization in Manchu are reasons to incline us to see in the former process a positive movement of increase of consonants and not their loss.

As to the aspiration and further formation of glottal consonants in Northern Tungus, we may observe this phenomenon in the case of «loan-words.» So we have, xulo (Ang. Tit.), hulo (Nomad Barg., Pop.,)_«the tinder,» cf. ula of the Buriats; hek (Transb. Tit)—«ex!» from Russian; hikin (Turn.)—«the cow,» «ox»; cf. ixan of Manchu; (it may be noted that in Nuichen the i is bilabialized—wei-han (Grube) (restored by P. Pelliot [op. cit., p. 240] as vihan), I might also quote the case of xorin (Goldi) corresponding to orin (Manchu and Mongol), but I do not want to do it, for in Mongol it is sometimes met with as xorin (cf. Dahur, Ivan.; Mongol, Rud.), and in this form it might be received by the Goldi direct from these sources. However, in Nuichen it is wo-lin (Grube) (i.e., *worin). Indeed, the number of foreign words with the initial vowels aspirated in the Tungus dialects is limited: for (1) not all words «need» to be aspirated; (2) the Tungus usually become familiar with the foreign phonetic systems (cf. the above-quoted case of the Birarchen f), especially in the case of the «non-aspiration» of vowels. The aspiration affects different words in different dialects. This has already been shown in the instances of Goldi aspiration. I have already suggested in my previous publication that the aspiration is correlated with the existence of expiratory and musical accents and length of vowels. So that the aspiration may be regarded as an unconscious process of «preservation» of vowels, which method functionally corresponds to the accentuation of vowels. I may here give an interesting instance from the Goldi, where we find xi (Goldi, Grube) corr. to usi, uhi, uxi (of various Tungus dialects), use (Manchu Writ.), wuze (Manchu Sp.)—«the thong.» The variations of Goldi xi may be supposed to be as usi→us'i→uhi→uxi→perhaps wxi→xi. This instance shows what may happen if the initial vowel is not «protected» by the aspiration and another vowel is accentuated, as it is in some Northern Tungus dialects.

72. In reference to the Mongol in his paper «Der Lautwandel im Mandschu und Mongolischen» (Journal of the Peking Oriental Society, Vol. IV, Peking, 1898) and in reference to the Olcha in a later publication on the Olcha language.

73. Cf. «Les Mots, etc.,» op. cit.

74. He defines it as «bekanten allgemeinen lautentwicklungsgesetz» (op. cit., p. 10).

75. Cf. »La Methode, etc.,» op. cit., p. 99.

76. In my papers published in Rocznik Orjentalistyczny, Vols. IV and VII.

77. One takes on one's self a great responsibility when one formulates new «laws» of science. First of all, the idea of «law» must be clear; for otherwise, if a certain tendency or a statistically frequent occurrence be taken for a «law,» this would merely show how small is one's respect for scientific laws. I believe that G. Ramstedt did not for a moment suppose his hypothesis was a scientific law. Second, the persuasiveness of a hypothesis when the latter is called a «law» can increase only in the eyes of persons who are not familiar with the subject. In this way, such an abuse of scientific terms may become, for them, misleading. Not in a lesser degree one must disagree with A. Sauvageot, who styles his observations, on the regularity of certain linguistical phenomena, «les lois statistiqnes.» That such an inaccuracy exists in the ideas of laymen and their language is a fact, but no one who is familiar with the terminology and scientific meaning of «statistics» and «statistical» would allow himself such an inaccuracy in a serious publication. It is far from me to take on myself a defense of purism, but such an abuse of terminology reveals the methodological side of the work discussed here, and as such it is worthy of attention. In fact, in A. Sauvageot's work one may observe some little (statistically) material which, when checked and recognized as reliable, may perhaps be used as good material for statistical analysis, but in his work there is no minor trace of statistical analysis. How can one speak of «statistical laws»? I point out this detail, for if the abuse of terminology continues it will bring further confusion into the simple problem of the Ural-Altaic languages. It is especially serious in the given case, for the work of A. Sauvageot is not an outcome of his own efforts only, but also that of his senior colleagues, so the abuse of terminology is not a mere lapsus lingua. Some authors suppose that the «linguistical laws» are not like other scientific laws — they cannot be accurate. But this is no reason why the term «law» should be applied to mere hypotheses and tendencies observed. What term, then, will be used when the actual laws are discovered?

78. Amongst the Manchus, as well as amongst the Birarchen, and Goldi this kind of dwelling is now built up in the form of a semi-underground house of Chinese type. Amongst the Northern Tungus living on hunting it is never used. According to tradition, this kind of dwelling was not originally of Chinese type. It seems to belong to the Paleasiatic complex.

79. ln most of the Northern Tungus dialects it is jeyin (Barg., Ner., Bir., Kum., Khin., RTM, Mank.), johin, jahin, jehin (Irk., Ang. Tit.), jegin (Neg. Sell.), jagin (Ur. Castr.) (cf. juyen, etc. [Buriat, Podg.], jisun, etc. [Mongol Rud.]).

80. That Manchu -xi corresponds to Tungus -rgi and Goldi -ga can be supported by other evidences. These are not suffixes. In Manchu Sp. we may expect to have jeye, or even veye. I have not happened to find this word in my records.