Part 5

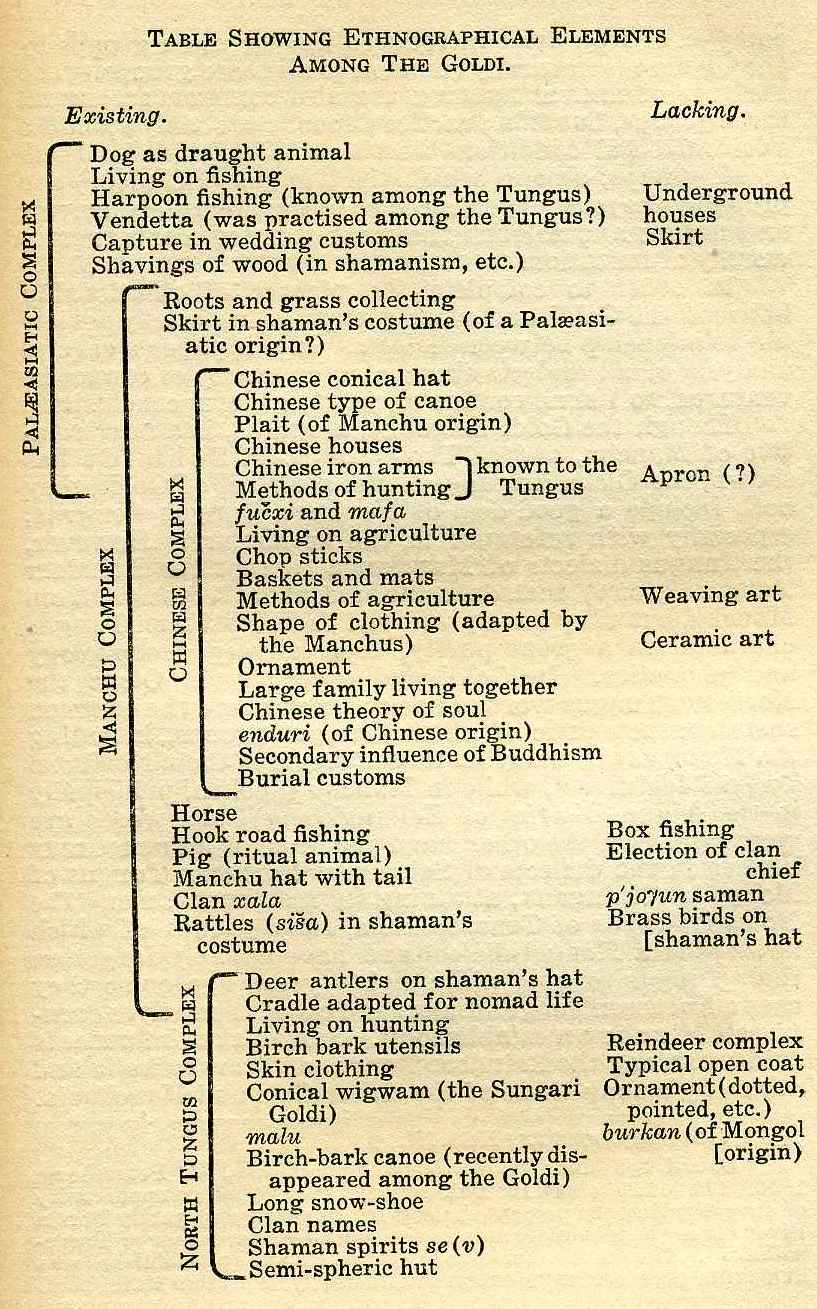

The above comparison of various ethnographical elements composing the Goldi complex may be better seen from the Table. The material for this table has been taken from the present paper. I am intending to show neither the proportion of elements and complexes borrowed by the Goldi, nor their practical importance in the Goldi complex. It is beyond any doubt that a replacing and disappearing of some complex, for instance that of reindeer, may result in a general change of equilibrium; on the other hand, a lacking of fucxi or burkan [69] shows but historic influences in the past. Yet the number of complexes and elements may easily be enlarged or reduced when desired. So the elements with reference to their importance in the Goldi complex are not adequate ones, but they are however typical as classificatory characteristics. Owing to the technical difficulty of printing and arranging the table, I have not separated the elements common to the groups I compare and Mongols. These elements are mostly included in the Manchu complex which is quite natural, the Manchu complex being a resultant from various influences including that of Mongols. I want to add that it may happen that some characteristics should perhaps be re-grouped [70]. However, these details do not change the scheme shown in this paper.

From the comparison of the Goldi with the Manchus and Northern Tungus it may be seen that from many points of view the Goldi ethnographical complex is close to that of the Manchus, but it also includes elements known among the Reindeer Northern Tungus and unknown among the Manchus. Yet some elements characteristic of the Amur River Paleasiatics' complex are met with among Goldi. The elements common among all groups and the Chinese are not numerous.

So for instance the complex of iron arms introduced among these groups by the Chinese is naturally common to all these groups. The methods of animal hunting are also common among all these groups, but this practice depends probably upon the environmental conditions and local adaptation to them of all groups, among which the Tungus (Reindeer) are probably the most experienced as living almost exclusively on hunting and as such the most adapted, consequently worthy of imitation.

In order to complete the picture of relationship between the Goldi and other groups let us briefly review the relationship between dialects. In this paper a careful analysis of all dialects illustrated by examples cannot be ventured, so I shall confine myself to general conclusions.

Though the Goldi language, as stated, is a near relative of Manchu, and as Professor P. P. Schmidt has shown, the Olcha language is also a dialect of Goldi, they both include a good deal of Northern Tungus elements, especially with reference to the vocabulary. However, the Tungus dialects of Manchuria (except the Reindeer Tungus group) include some recent borrowings from Manchu, but they have preserved their Northern Tungus character in a great purity, especially in morphology and phonetics. In Goldi and especially in Olcha the Northern Tungus words (I do not mean here the common roots characteristic of all the Tungus groups, including the Manchus) in many instances preserve their Northern Tungus features [71], while in Manchu (spoken, principally in the Ajgun District of Heilungkiang) such words are very rare. On the other hand the Mongol influence may be seen in the dialects of Solon and Northern Tungus of Mongolia (Khingan), attaining its maximum among the Nomad Tungus of Transbaikalia, some groups of which now speak a Mongol dialect and have entirely forgotten their Tungus tongue, while eighty years ago or so they used a Northern Tungus dialect and called themselves evenki, as A. Gastren established [72]. Some Yakut influence is evident among the Reindeer Tungus of Transbaikalia and naturally among those of the Amur Gov. and Manchuria. However, among the Reindeer Tungus of Transbaikalia some Mongol influence has to be accounted for. Thus the relationship between these dialects and languages may schematically be formulated as follows:

(1) Southern Tungus is preserved inManchu Lit. and Manchu Sp., the latter being but very slightly influenced by Northern Tungus;

(2) Goldi and Olcha, also Sungari Goldi are close to Southern Tungus, but include very numerous Northern Tungus elements;

(3) Tungus of Manchuria (except the Reindeer Tungus) is a Northern Tungus language, including some recent Southern Tungus elements;

(4) Reindeer Tungus of Munchuria is a Northern Tungus dialect with traces of Yakut;

(5) Tungus of Mongolia and Solon, also Tungus of Transbaikalia, Barguzin, Mankova, and Borzia groups are Northern Tungus dialects with numerous traces of Mongolian;

(6) Nomad Tungus (Urulga, Chita District of Transbaikalia, and some other groups of the same region) is a Mongolian dialect with traces of Northern Tungus.

Besides the Northern Tungus element in Goldi language [73] a considerable amount of non-Tungus (Northern and Southern) words is seen. The origin of the latter may be looked for in the Paleeasiatic languages which, theoretically speaking, may have influenced the Goldi language. As Professor P.P.Schmidt says, «Goldi is still nowaday the international language between different peoples of the lower Amur basin», thus it is natural that this language is influenced by Palseasiatics. It is also probable that some Paleasiatic groups have been swallowed by the Goldi (and the Manchus).

Anthropological data indeed would provide us with the most convincing and positive evidences as to the Goldi physical (anthropological) origin, but for the time being I shall abstain from any attempt of this kind for the reason that the anthropological data are still unpublished [74]. It may be, however, noted that an intrusion of Giliak element among, for instance, Olcha, is beyond any doubt — Olcha are a group mixed up of the Goldi and Giliaks. The Ainu influence upon the Goldi is also probable because the latter used to have Ainu as slaves and as I have shown a slave [75] in the system of this type of social organization may easily become a member of the clan in which he formerly was a stranger.

Let us now see how might the process of Goldi formation occur. We have seen that the Goldi are a group showing from all points of view a mixed character and origin. This might happen only in the case of spreading of a powerful complex among a population with an inferior (at least technically) culture, i.e., a culture less complex than the first. Such a superior complex might be that of the Manchu ancestors, let us call them Southern Tungus, who since an early period borrowed elements of the Chinese culture, consequently could easily influence their neighbours. On the other hand, as the influence of the Northern Tungus over the Southern Tungus and perhaps that of the Palseasiatic groups which already possessed a technically superior culture and settled mode of life, might be effective but in the sphere of phenomena in which the Northern Tungus' competence could not be competed, viz., the hunting. But it is also evident that the hunting methods as a complex do not require a complete change of life from the part of a settled group. If it be so, then the borrowing of cultural elements from the Northern Tungus might have had a very limited sphere. These general considerations based upon the facts now observed among various groups in this part of Asia, are also intelligible from a general theoretical point of view, while the hypothesis of a tungusification of the Southern Tungus and the Amur River Paleasiatics stands in a complete contradiction to the general process of cultural successions.

The present ethnographical (and linguistical) features of the Goldi may be thus explained as a process of swallowing of the Northern Tungus, who went from the north and west (the secondary Tungus movement) southward and eastward, by the Southern Tungus and perhaps Palasasiatic groups. In fact, the Goldi complex is very rich in Northern Tungus elements both in culture and language, but at present it is closer to that of the Manchus than to any other group and it posesses some elements of PalEeasiatic culture unknown to the Manchus [76]. It may be here added that some of these elements are very essential as playing a great role in assuring the ethnographical equilibrium. It may now be asked when might this process have occurred?

Professor P. P. Schmidt supposes that the Negidals, a Northern Tungus group, living in the lower course of the Amur River basin, were for many centuries neighbours of the «Manchurian Oroches» [77], Goldi and Olcha and he supposes with good reason that the Goldi have separated the Negidals from a kindred group of Oroche. However, the Orochi (in the Maritime Government north of the Botchi River falling into Japanese Sea), asL. J. Sternberg has shown [78], went (naturally, from north or west) with the reindeer that they lost in their present area during the last (?) century. So this group is now in the process of losing its original reindeer culture (the Northern Tungus), as Negidals do. On the other hand, the process of losing this complex may also be observed in a very advanced stage among the Udehe of Ussuriland. This group have preserved their original complex in a much lesser degree that Orochi and Negidals [79]. Yet, the original Northern Tungus complex is better preserved among the Tungus of Manchuria. A group called Kumarcen living in the basin of the Kumara River assert that they formerly possessed reindeer and about a century ago or so they lost it. This group as well as the Tungus of Khingan (in Mongolia) pretend to descend together from the north by an accident (a usual explanation [80]) being divided into two parts: Khingan Tungus and others. This event took place, according to a tradition two or three centuries ago, i.e., probably after this region had been abandoned by its former population, viz. ducery, dahury, goguli of early Russians (in the XVIIth century) [81]. The languages of Kumarcen and the Birar Yamen Tungus as stated do not show any essential differences for dissecting them into two different dialects, they are mere sub-dialects. But the Tungus of Birar Yamen assert that they (at least a part of them) have come from the lower course of the Amur River and, as shown [82] they include some clan names known among the Goldi, especially those living in the eastern part of their territory. The Birar Yamen Tungus, however, about sixty or seventy years ago — used to have a hunting territory reaching as far as the Lake Hanka in the South Ussuriland (!) and that hunting territory belonged to the dunagir clan. They passed then across the Sungari River and the territory occupied by the Goldi. In the South they were thus in contact with the Goldi and probably with the Udehe. With the Kumarcen Tungus they also have common clans. It is, therefore, probable that the whole mountainous and forest region of the Amur River basin was at some period occupied by the same group (or wave) of the Reindeer Tungus, a part of whom migrated later northward from the Goldi area owing to the same cause which had also compelled the Udehe to migrate northward. However, a continuous southward movement of the Tungus is observed at present. Moreover, the instance of the Amur Government Reindeer Tungus who migrated in 1916 or so to Sakhalin is similar to that which occurred some seventy-five years ago when a Reindeer group of the Amur Government migrated southward and occupied the North Western part of the Manchurian Plateau (the basin of the Bystraja and Albasixa Rivers). As stated the dialect of the Reindeer Tungus of Manchuria and that of the Reindeer Tungus of Amur Government who migrated to Sakhalin show some Yakut influences which indicates that these groups were during a long time in close contact with Yakuts, while the dialects of the Kumarcen and the Birar Yamen Tungus have no striking signs of direct Yakut influence [83].

Let us go farther. There may be thus established that the last wave took place during the XIXth century being now represented by the Reindeer Tungus of Manchuria, Amur Gov. and Sakhalin (except Oroki who had come earlier). The preceding wave — in the XVIIth century — is represented by the Tungus of Manchuria (except the Reindeer Tungus) and Mongolia (except Solon) who (all, or at least a part of them) have lost their reindeer within the memory of the previous generation. The waves represented by the Negidals of the low Amur River basin and Orochi of Port Imperial might have taken place before the XVIIth century but after the Xth century, as Professor P. P. Schmidt supposes. I think that this event took place during the XII and Xlllth centuries. In fact at that period some important catastrophe occurred in the basin of the Amur River: several cultural centres, large cities and fortresses [84] were destroyed by an invasion in the basin of the Sungari and Amur rivers which was at that time occupied by a group with a highly developed culture (not that of the above enumerated groups). The Mongols are responsible for this catastrophe. So when, according to their practice, they had swept out the population, they went away and very soon fell down.

The empty lands were occupied probably by newcomers — the Negidals, Orochi and perhaps nugal who partly preserved their reindeer and the reindeer complex but have lost it as a whole. If it be so, then the Amur River in its lower course had already been at a former period, at least to a certain extent, occupied by some other Northern Tungus group. There the Northern Tungus who had come to the basin of the Amur River before the XIIth century, probably via the Amur River, were ancestors of the Goldi, probably Udehe, perhaps Solon of Manchuria and Xamnagan, also their kinsmen in Transbaikalia [85]. This movement again corresponds to two historical events of importance, namely, the downfall of Bohai [86] in Northern Korea and Manchuria, also Ussuriland and rising up of a new ethnical group of Kithan [87]. The most advanced groups into the south naturally went to the Amurland and spread as far southward as the territory of the former Bohai. This southward movement was also stimulated by other Tungus groups which pressed the first ones from the north. However, the low course of the Amur and Sungari rivers were already occupied since the first Tungus migration from the South, which continued a very long time and found its traces in Chinese annals. The first migration when the Chinese spread eastward, according to my hypothesis, led the Tungus or rather pro-Tungus from their original home in the present China, between the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, to South Manchuria and farther [88]. This movement combined with the back movement from the north in many respects resembles the phenomenon French geologists call charriage. The ancestors of Goldi finding a population very advanced from a cultural point of view, were compelled in conditions of river life—to change their habits and customs by adopting another complex. So, the ancestors of Manchus being already at a high stage of sinification, influenced the newcomers who, however, lost their former culture not at once, but gradually. The Udehe being isolated in an inhospitable corner of Ussuriland have preserved their original complex better than Goldi, but the latter, in spite of a strong Manchu influence, had formed a distinct ethnical unit which later on was incorporated into the Manchu (the Southern Tungus) body as ici mandju (Modern Manchus), the true Southern Tungus being distinguished as fe mandju (Ancient Manchus), while the Kumarcen, Birarcen, Khingan, Solon continued to preserve their semi-independent existence, being incorporated as a people of an inferior kind (in a lesser degree sinificated), and the Negidals, Udehe, and others were left independent as a lowest kind of Manchu subjects [89].

The approximate date of the appearing of the ancestors of Goldi also Udehe and perhaps Solon in the south may be supposed to have been previous to the downfall of the Bohai power, which occurred about the Xth century. However, the control of the population of former Bohai by the Kithans and later by Nui-chen could not be very effective in the northern and eastern confines of their influence, because Kithan's and Nui-chen's attention was always drawn to the south and west where they had to watch a powerful China and Mongol-Turks. So, these territories were probably considerably depopulated and were occupied by the Northern Tungus. This was probably the first wave of the Northern Tungus caused either by a natural increase of the Northern Tungus (transition to a superior culture — reindeer breeding) or by an invasion of Siberia by an alien group.

[69] Cf. above, footnote [48]. (Back)

[70] Owing to the lack of a library I have in composing the present paper used in some cases my memory and notes which naturally are incomplete and cannot replace a library. Moreover, the origin of some elements has not yet been established by investigations. (Back)

[71] Vide Supplementary Note III. (Back)

[72] Grundzuge einer tungusischen Sprachlehre, St. Petersburg, 1856. I have lately been fortunate enough to have had an opportunity of investigating the present dialects of Mankova and partly Borzia River (in my approximate map in the south-eastern corner of Transbaikalia). Though the Mankova dialect as Castren established was at his time preserved more or less satisfactorily its present state shows the most evident Mongol (Buriat) influence, which has gained this dialect much more than it was observed by Castren. It is interesting that the group of the Borzia Tungus have better preserved their tongue, which probably belongs to the same dialect as the extinct tongue of Urulga, thus different from that of Mankova. It is also probable that some groups of this Tungus branch have been included into the present Dahurs or vice versa. One thing is evident that the Nomad Tungus, of Transbaikalia are in some relationship with Dahurs. E. Ysebrants Ides visiting Eastern Transbaikalia by the end of the XVIIth century learnt from these Tungus (directly or through Russians) that they pretended to descend from Dahurs. This migration and connexion with Dahurs is still alive in the folk memory, as I have seen myself. However, by quoting these facts I do not intend to show that originally Dahurs were bound (ethnically) with the Northern Tungus. (Details concerning history and political side of this migration may be found in J. F, Baddley's Russia, Mongolia, China. Being some Record of the Relations between them, etc. 2 Vols, London, 1919). (Back)

[73] A further investigation of Goldi language will show in what degree the Northern Tungus elements are represented in this language. I shall not be surprised if it is classified as a Northern Tungus dialect influenced by Southern Tungus. As shown, Udehe language shows some intermediary characters; in a lesser degree the same may be referred to Orochi language. (Back)

[74] Theseriesof the Goldi measured by L. J. Sternberg is known to me. As far as I remember, the analysis of this series showed that the Goldi include at least two different types, one of which is close to my hypothetical type delta. It is interesting that the Manehus suppose Goldi to include some element » like Mongol people». It is also evident that the type gamma is a very common element among the Goldi. But the presence of type beta is also probable and physiognomically some Goldi are typical representative of this type. The small series of the Northern Tungus of Manchuria measured by me shows a mixed character, different from that found among the Reindeer Tungus of Transbaikalia. They seem to approach (physiognomically) the Goldi. As to the types and their characteristics, also various instances of mixing up of different groups, including type gamma cf. my Anthropology of Northern China, Extra Vol. II, 1923, N.C.B.R.A.S., and Anthropology of Eastern China and Kwangtung Province, Extra Vol. IV 1925, Shanghai. (Back)

[75] Cf. Soc. Org. of the Manchus, etc., p.106. (Back)

[76] The Manchu complex includes some Palseasiatic elements which among them seem to have been very early borrowings. (Back)

[77] It is not clear which group Professor P. P. Schmidt speaks about. By the way it may be noted that the name oroci in Tungus means: having residence, having seat, etc. i.e., local. So for instance, Birar Yamun Tungus say: bi eri buhadu oroci bisim, i.e. I (in) this locality «having residence» am. This term translates perfectly the term nani of Goldi (see footnote 1). In this case the name orocen («having reindeer», analogous to murcen—«having horses») and the name oroci (also perhaps Manchu oronco (oroncun) associated with » wild» and «wild goat» — orongo) are phonetically-very close but genetically they are of an entirely different origin which once more must warn ethnologists from an appelation to little known languages. (Back)

[78] I quote from S. Brailovsky, op, cit. (Back)

[79] Vide Supplementary Note III. (Back)

[80] Cf. E. N. Shirokogorova, North Western Manchuria. A Geographical Sketch, etc., in Publication of the Hist.—Phil. Faculty of the Far Eastern University, at Vladivostok, Vol. I. pp. 109-155. (Back)

[81] With reference to ducery I want to add a few words in addition to Supplementary Note X in Soc. Org. of the Manchus. etc. p. 175, where an error has crept in: in line 8 instead of p. 44 read p. 14 and p. 37 and instead «affirms „must be „shows.“ In the eyes of Jesuits the Manchus included various groups. However, it is evident that ducery is not a Manchu group in a strict sense of this term but a Goldi group manchufied and perhaps included into ici manau (cf. above p. 126, Footnote 11). So it is probable that the name ducery was referred by Russians to the Goldi, perhaps Solon, etc. and not to the Manchus whom they styled bogdojcy. Without this hypothesis it is not clear, why Russians used both terms ducery and bogdojcy with reference to one and the same group—the Manchus. As I have shown both terms are borrowed by Russians from the Northern Tungus whom they met first, and it is hardly likely that the Northern Tungus who were versed in the political and ethnical relations observed at that time in their area did not distinguish the Manchus from other groups. (Back)

[82] Cf. above p. 139. I think, however, that they lost their reindeer long ago, much earlier than L. Schrenck thinks. In their folk-lore, also that of the Amur Government Reindeer Tungus they always figure as having horses. So, -R. Maack (op. cit.) found the Tungus of Birar Yamen at their present territory as possessing horses. Du Halde (the end of the XVIIth century) mentions the reindeer breeders only in the basin of the Zeja River and asserts that Manchus called them „orotchon, d'un animal oron“ (op. cit. p. 37) which is absolutely right. It is interesting that another group of the Reindeer Tungus in the Sakhalin Island who are close to Orocni of Port Imperial he calls Ke-tcheng-ta-se, referring this name also to the Tungus of the Amur River (op. cit. p. 12). (Back)

[83] Among the Reindeer Tungus of Amur Gov. a late Yakut influence might also occur, for Yakuts spread along with these Tungus from the Yakutsk Gov. southward and went with them to Sakhalin. (Back)

[84] E. Ysebrants Ides (op. cit. p. 47) mentions archaeological remains of Nuichen period (according to local tradition) in the valley of the Argun River. Lately some of them have been partly excavated and described (unpublished) by local (Transbaikalia) amateurs of archaeology (A. K. Kuznecov, Colonel Orlov, and others). Du Halde mentions several remains of this period within Manchuria. Very numerous remains of this period are also found in the Ussuriland (cf. Th. Th. Busse and Prince Kropotkin, Ancient Remains in the Amurland, Memoirs of the Vladivostok Branch of the Amur Section of the Imp. Russ. Geogr. Soc, Vol. XII, in Russian, 1908). In the middle course of the Amur River I have excavated and observed several remains of this period. Lately W. J. Tolmacheff (Historic Manchurian Relics. Ruins of Peich'eng, in Manchuria Monitor No. 1, 1925, Harbin, in Russian with a note in English) has given a description of a provincial capital of Nui-chen destroyed at the same period. (Cf. also A. Baranov's papers in the Bulletin of the Museum of the Manchuria Research Society, No. 1, Harbin, 1923 in Russian; and in Bulletin of the same Society, No. 3, June, 1923, Harbin, in Russian). (Back)

[85] Some Tungus group before the Xllth century lived northward from Nui-chen, i.e., in the region of the Sungari (or Amur?) River. They possessed all kinds of domesticated animals, especially oxen which they used for mounting. They also knew the birch bark wigroth, op. cit. p. 90 instrument for challenging deer, etc. (J. Klapwam, the wooden), which indicates at a transitory character of that complex. It is possible that here we have the ancestors of the Goldi or Solon. But it is also evident that that group had already borrowed many elements of the Southern Tungus complex. De Saint Denys (op. cit. 430) says that hoa is not the birch bark, but the bark of another resinous tree. At present the Nomad Tungus of Transbaikalia, who migrated from Manchuria, use the bark of the larch tree for covering their huts which are not of a conical form but square with a roof and an aperture in it for smoke and light. The same group mentioned in Chinese chronicles was known as horsebreeders, i.e., just like the Nomad Tungus and Solon called by their Northern Tungus neighbours murcen, which means „possessing horse,» However, along with the hut above described the Nomad Tungus and Solon use a Mongolian semi-spheric tent covered with felt, which is probably of a late origin. Another detail of interest is the use of animal skins for a small and light canoe. This kind of canoe is mentioned by the present Northern Tungus of Manchuria folk-lore borrowed from Solon and Dahurs. E. Ysebrants Ides (op. cit. p. 48) used this kind of canoe when he crossed the Gan River in the territory of Solons and their kinsmen. The territory indicated by Chinese chronicles with reference to that group lay in the vicinity of the present Solon area. It is very probable that they were also included into the political organization known as Nui-chen (Cf. Soc. Org. of the Manchus, etc., Suppl. Note X.) From these facts it may be inferred that this group of Nui-chen mentioned as Shih-Wei was a Northern Tungus group which entered in touch with the Southern Tungus and the language of which was different from that of the Southern Tungus. De Saint Denys having based himself on Ma-touan-lih's testimony supposed them (op. cit. p. 345, footnote 73) to have been kinsmen of Kithans. D u H a 1 de (op. cit. p. 14) supposed that Solon Tungus are Manchus or better, their ancestors who escaped being destroyed by Mongols by a retreat (Nui-chen) westward to their (Solon) present {the XVIIth century) habitat. If it be so, then all Nui-chen were a purely Northern Tungus group which is, as we now know, not right. But it is beyond any doubt that Solon played some role in the Nui-chen political organization. H. H. Howorth (The Northern Frontagers of China,— in a series of of papers in J.R.A.S., particularly Article X. The Kin or Golden Tartars, in Vol. IX, 1877, pp. 243-290) who did not add any new facts to the history of Nui-chen, has clearly emphasized the difference between Wild Nui-chen and Civilized Nui-chen and the process of their evolving into the Nui-chen organization. Moreover du Halde says that Solon had their town called «Niergui», which perhaps may also be connected with a Dahur clan nirgir. The nirger soldiers (cuxa) are mentioned in the Manchu folk-lore in an epic poem which is assigned by Mandius to the period of the Ming dynasty or earlier, and it may be understood that nirger cuxa were in some connexion with Solons and Dahurs. From the above facts it is clear that several groups of Southern and Northern Tungus families took their part in the Nui-chen organization and the Northern Tungus lived a long time before that period. (Back)

[86] Was this power of Southern Tungus or Palaaasiatic origin is not yet established. There is an indication that Korean emigrants had something to do with the beginning of this political formation. I am rather inclined to consider it as a Paleasiatic formation because the Southern Tungus were very active in Southern Manchuria and Northern China, while the territory of Bohai was separated from Southern Manchuria by Koreans who since the earliest time were already playing a very important role as a well organized and influential group and whose influence spread as far as the eastern slope of the Sixota Alin mountains occupied by a mysterious group. (Thiou-mo-leou of de SaintDenys, op. cit. pp. 271-273, and Teou-mo-liu of J. Klaproth, op. cit.) (Back)

[87] Several authors supposed Kithan to be a Tungus group. Chinese sources even assert that their language and that of Moho and Shih-Wei was the same. As I have shown Shih-Wei seem to be close to the ancestors of the Solon and Nomad Tungus of Transbaikalia, who belong to the Northern Tungus branch of the first wave which occurred probably before the Xth century. However, Moho and Kithan are in many respects different, as well as Shih-Wei, and the assertion of the Chinese as to their language seems to be little believable. The Kithans were living in Southern Manchuria and South Eastern Mongolia. It is beyond any doubt, they fell under a strong Chinese influence. However, before that they possessed some features similar to those of Moho (J. Klaproth, p. cit. p. 87). Thus, it is not clear whether Kithans are of Southern Tungus origin, or of a Northern Tungus origin, or connected with Mongols. The opinion of authors varies. Some consider them to be Tungus, while others are inclined to see in them a Mongol group. Considering the succession of various groups in Manchuria and Mongolia I am rather inclined to believe them to be a group alien to the Northern Tungus. In fact such a hypothesis would require another, namely a very early migration of the Northern Tungus (at least some centuries before they came to power, i.e., about the IIIrd century A.D. when Hiunnu were defeated by the Chinese). Even a deciphering of the Kithan inscription (cf. T'oung Pao, Vol. XXII, No. 4, pp. 292-301, also Professor Kotwicz, Les «Khitais» et leur ecriture, in Rocznik Orientalistyczny, Tome II, 1925, Lwow, pp. 248-250) lately (1922) found cannot perhaps disclose the original ethnical affinities of Kithan, for since they began to play a political role they also might have changed their language. Professor P. Pelliot (op. cit. p. 146) asserts: «les K'i-tan parlaient d'ailleurs une langue apparentee au mongol, encore que fortement palatalisee.» It is interesting that the language of Dahurs, who themselves pretend to be direct descend-ents of Kithans,beinga Mongol dialect as Professor Kotwicz points out, bears some characters which approach that of the Mongols living in Amdo. «Whence he supposes that the Dahurs (Kithans) did speak the same language as that of Mongols in the XIIIth and XIVth centuries. Thus, the question who were Kithans is not at all clear. (Back)

[88] Vide Supplementary Note IV. (Back)

[89] According to S. Brailovsky (op. cit.) the Udehe told him that they had been subjugated by Manchus by force and it is interesting that they have preserved their two plaits as a sign of semi-independence. So, probably they have been manchufied in a much lesser degree than the Goldi who were incorporated at once into the Manchu military organization. It also indicates that the ethnographical differences between the Southern Tungus (Manchus) and Udehe were at that time still greater than at present, which is due to the Chinese influence on both of them. With reference to a previous period it may be remembered that Nui-chen were very mixed (cf. above, footnote [85]). They distinguished among themselves three groups of clans, one of which for instance lived in the eastern part of the Nui-chen territory, i.e., in the territory at a previous period occupied by some group distinct from the Southern Tungus and Paheasiatics (cf. footnote [86]). The same territory was later occupied by the Udehe. Moreover, as stated in the formation of Bohai, various groups (Koreans, etc.) took part. So, the mixing of some Northern Tungus groups into formation of Nui-chen, besides the above mentioned, is very probable. It is thus quite possible that the Udehe, at least a part of them, were also included into Nui-chen and later into the Manchu organization, as Palladius thought. (Back)