43. Human Soul

In Chapter IV I have given a general description of the soul and its complex its complex organization. We have seen that the soul is not a very stable element of man (and animals), and owing to its complexity it may gradually disintegrate without resulting in a complete extinction of the living organism.

The Tungus need proofs of the existence of soul and its complex organization. The proofs are numerous. In the analysis of the process of proving we shall now find how these complex souls exist and which roles they play. The first soul of the Manchus or wunengi fojengo and the first soul of the Tungus of Manchuria may be easily observed in the manifestations of exterioration [277] of the soul, e.g. the loss of consciousness, not followed by death, travelling during dreams, communication at a distance, intrusion of the soul into other people, etc. These facts are so numerous that the Tungus (including the Manchus) do not hesitate as to the reality of the existence of soul.

It is different with the second soul of the Tungus and third soul, — olorg'i (external) fojengo, — of the Manchus. However, its existence may be also proved. Its existence is seen, so to say, indirectly, but the Tungus may sometimes see it directly and experimentally. For instance, among the Birarchen a man once found a piece of broken mirror. When he looked into it he saw instead of his own face a mule's head. Being disgusted, he naturally threw away the mirror. However, competent people explained the case; namely, he saw his own soul which in previous reincarnations might have been that of a mule. In fact, from time to time the Tungus find such mirrors in which they may see their own souls. Indeed, there the question is about the second soul, which is considered by some Tungus to be the principal soul after the loss of which it is impossible to revive. Its traces can also be seen when it leaves the body on the seventh day after death. On this day at night the Tungus put some ashes or sand on the threshold or in the entrance of wigwam and see what kind of foot prints are left by the soul. These may be that of a man, a horse, a roe-deer, a chicken, or other animal. The activity and existence of this soul is also supported by the cases when this soul introduces itself into living people who may tell, after their own experience received in this state, what is the nature of this soul and what it wants. Indeed, the theory of metempsychosis greatly helps to support the theory of soul in general, for it can be found in the books written by clever, educated people and yet sometimes under the inspiration of the spirits. Among the Manchus this soul may also leave the body during sleep, so that the Manchus as well, form their idea about its existence from the fact of dreams. It ought to be pointed out that sleep is explained by the Manchus as due to the retardation of the blood circulation and not to the absence of this soul, while the loss of consciousness is explained as due to the departure of the first soul, which may also leave people because of a sudden fear.

The existence of the third soul which for some time remains with the corpse and later stays with the members of the family amongst the Birarchen is proved chiefly by the experience of the people who often see their parents in their dreams, during hallucinations etc. However, the Manchus have no need to ex-plain it for, according to them, this returns to ongos'i mama for being given to other children. Some Manchus suppose that this soul remains with the corpse as it is amongst the Birarchen, but it does not go to stay with the family. In this case the first soul would be supposed to go back to ongos'i mama. So the function of ongos'i mama is production of souls. The question why the Birarchen needed this theory is that they did preserve their own idea that the SOUL remains with the family (clan) and they adopted the idea of complex soul and the idea of a spirit (om'is'i, ongos'i of the Manchus) which gives the souls to the children. The Tungus (Birarchen) do not stop their observation of facts which may be used for supporting the hypothesis of soul. They suppose that the soul may leave the body without causing direct death which may occur some time later. However, the soul which leaves the body is noticed by some animals who react in a special manner. For instance, the foxes and wolves in seeing a soul, begin to bark which, as known, is not common in these animals. This is also used as one of evidences of the exterioration of the soul.

The nature and organization of the soul may be still better understood if we consider the case of twins discussed by the Birarchen. Since the souls are given by omi'is'i to one child and since two children are born the soul must be divided into two parts: one part to each child. As long as the twins are alive they may have a single soul in common, but when one of them dies, the other child cannot be unaffected, since the two «partial» souls must go as one to the world of dead people and another to stay with the corpse. Owing to this both children twins usually die within a short period. Naturally the death of twins is used as proof of the existence of soul. Here it ought to be pointed out that the soul is stabilised rather late, so if one of children dies in early childhood another one may survive. Yet, if the twins already are adult the death of one is not so dangerous for the other, as it is in the middle period of childhood. However, I could not find out any explanation of the difference [278].

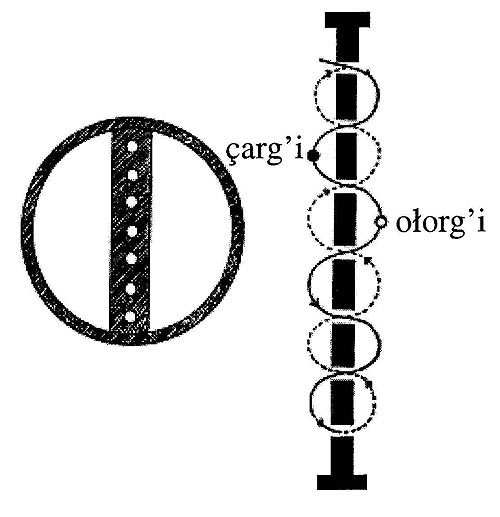

According to the Manchus, the soul may be located in different parts of the body. There is a circle in which is included a plank with seven holes [n'amen nadan sagga, i.e. circle (also heart) seven holes] [279]. The wunengi fojengo remains stationary, while carg'i and olorg'i are moving so that the first is always ahead of the second and they are always found separated by the «plank». They must not hinder their respective movements. If this movement is regular, the owner of the soul is well balanced and sleeps well. In case of fear, and similar conditions the movement of souls may be accelerated and thus the distance between them shortened which the person would feel. As result of fear the olorg'i soul may leave the body and the person would be sleepy and dreamy. The case of absence for a long time of one of the souls may also cause not only a feeling of uneasiness and confusion, but also a complete unconsciousness and even death if the period of absence should he extended over a certain time. So that for instance, the absence of carg'i and olorg'i will not be followed by death at once but the death will occur within a certain time. The liver also has something to do with the soul; a very brave person is supposed to have a large liver. However, if the liver is taken away the soul is not affected, so that liver has only a certain influence on, but is not the placing of the soul.

Amongst the Tungus of Manchuria (Birarchen and Kumarchen) it is supposed that the absence of the first soul may result in the loss of consciousness but when the second soul leaves the body there is no great chance to call it back and death is inevitable. It does not mean, however, that the corpse, which is not yet decomposed, cannot be revived. Such cases are known and they will be discussed later.

Among the Barguzin and Nerchinsk Tungus I have not been able to find out the details concerning the organization of the soul. They suppose that the soul has its history of migrations, for it is given to the new-born child by dajacan (which is a general term for master spirits) om’i nalkan at the moment when a soul leaves the middle world caused by the activity of spirits and natural senescence. However, since they recognize om'i, irlinkan, also an'an, etc., it is very likely that their system is a composite one, as that of Birarchen, and thus they also recognise the threefold nature of the soul.

If we describe the history of the soul, as it is understood among the Birarchen, it will run as follows. The child is born with what is received from the parents, namely, erga — the life-breathing and what is received from omos'i i.e. om'i — the soul, — the self-reproduction and growth energy. (This conception is rather new; it is connected with an originally non-Tungus complex.) The soul an'an in small children is not stable at all and at any moment may leave the body (an 'an — the «shadow, immaterial substance», is an old conception, as the stem preserved in Manchu fajanga||fojengo). When it is stabilized (the child becomes conscious) the soul — sus'i — consisting of three parts, settles. However, the first soul may occasionally leave the body without causing any great harm, except loss of consciousness, but it cannot leave for a long time. The second soul may also leave the body, but only for a short time as a long absence would result in death. This soul, after death, goes to the world of the dead and is at the disposal of immunkan and it may later be returned to this world to some male or female child or to an animal, or it may remain unemployed. The third soul remains with the body as long as the body is not decomposed. When it leaves the body it goes to remain with the family members. The conception of threefold soul is a new one, so that in the Birarchen conception different complexes are included: the old one of an'an, the new one of omi, and at last that of the threefold soul — sus’i.

The Manchu idea of soul essentially differs from that of the Birarchen. The ergen is received from the father. The threefold soul is given by the spirit ongos’i mama. The first soul is the true soul which cannot leave the body without causing death. The second soul may temporarily leave the body which results in dreams and loss of consciousness. The third soul also may leave temporarily without causing death. The third soul returns to the spirit of the lower world ilmunxan and it may be used again as the Birarchen believe. The first or second soul returns to ongos'i mama. The non-Tungus origin of this conception is evident.

The disturbances in the stability of the three

elements of the soul and their relation to the life-breath (erga), also

temporary leaving of the body by the soul, explains to the Tungus all cases of

individual trouble and at the same time confirms their conviction in the

correctness of their hypotheses. The methods of regulation of the life of the

soul will be treated in two other parts of this work, but now we shall proceed

to the possible activity and continuity of the souls.

277. I use here term «exterioration» in the sense of physical removal, displacement of the soul. The same remark refers to «exteriorate».

278. Perhaps this is connected with the idea that the threefold souls are received later. The opinions regarding this delicate matter are not fixed. Some Tungus suppose that the twins have two souls and thus the death of one of them will not be followed by death of the other. It may be here pointed out that the recent investigations as to twins have shown that the uniovular twins very often die about at the same period. Seemingly, this fact did not escape the Tungus attention and they explained it by their hypothesis of soul. Yet, since this tendency is not observed in biovular twins the facts also did not escape the Tungus attention whence we have their hesitation as to the possibility of a generalization of their hypothesis.

279. It is very likely that the Manchus borrowed their theory from the Chinese. In fact, «Yin Chow (1122 B. C.) killed Pi Kan and dissected his heart to see whether it had seven openings» cf. E. T. Hsieh A Review of China anatomy from the period of Huangti. C. Med. Journ., 1920. Anat. Suppl., p. 8.